One sunny morning in Kenya, a lively discussion between Divine Foundjem, Valentina Robiglio and Raphael (Rapha) Tsanga – three of our regional focal points – brought to light some of the challenges and opportunities of engaging diverse, and sometimes conflicting, stakeholders across Africa and Latin America.

Through their conversation – and especially some of the provocative statements the three made – several pieces of advice emerged for those planning to implement future projects:

- Map roles, interests and power

- Go beyond representation

- Balance law and legitimacy

- Acknowledge ‘difficult’ actors

- Create alternatives for youth

- Co-create a shared vision

- Recognize the agency of ILM practitioners

- View multi-stakeholder platforms as processes, not events

- Invest in invisible work

Listen in on the full conversation now, or skip to the highlights below.

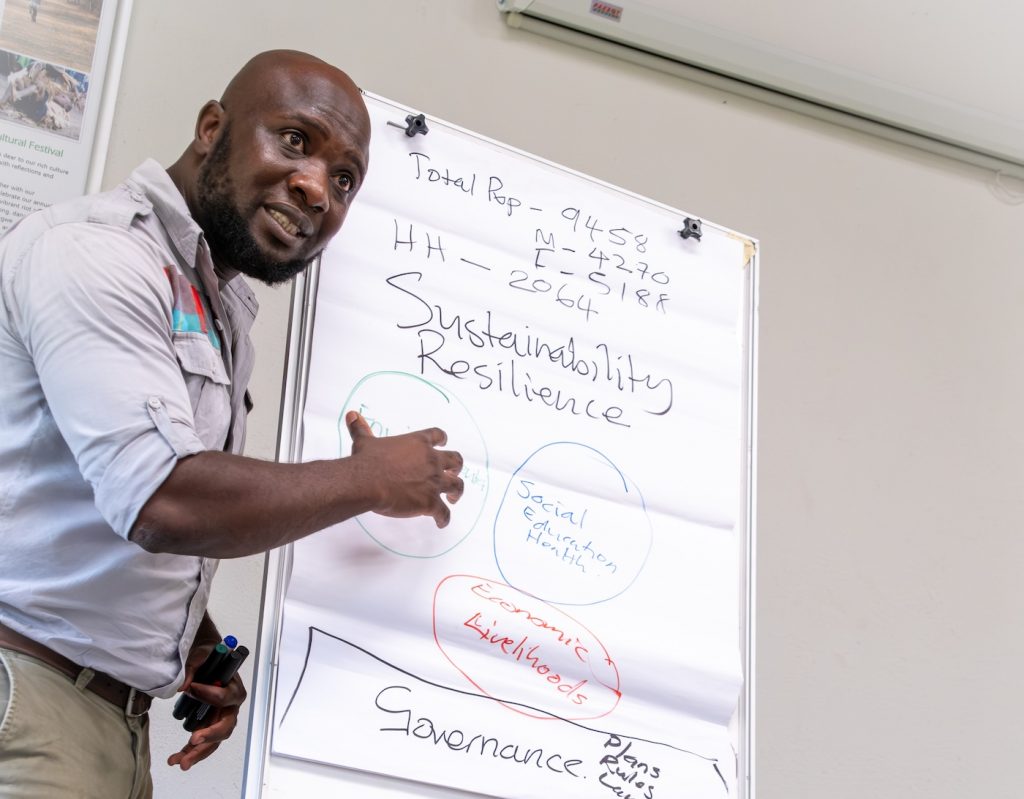

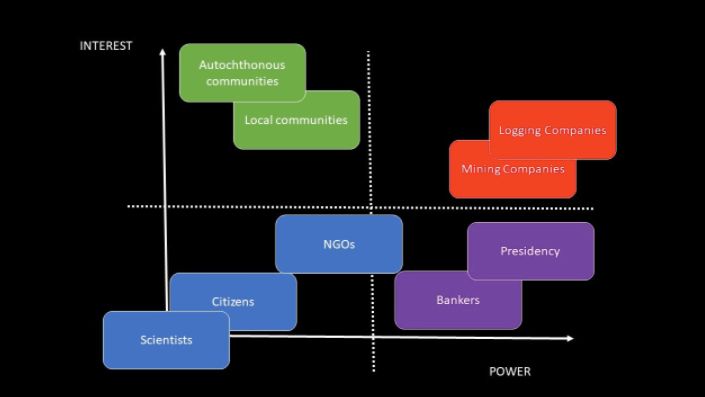

Map roles, interests and power

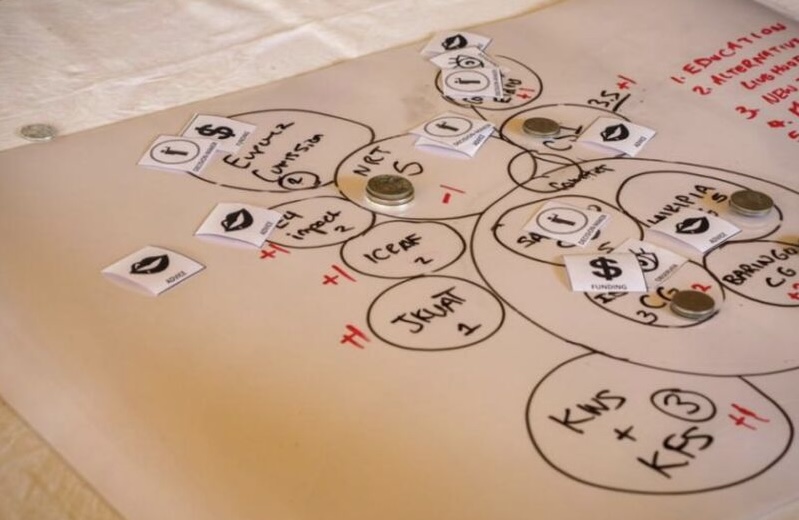

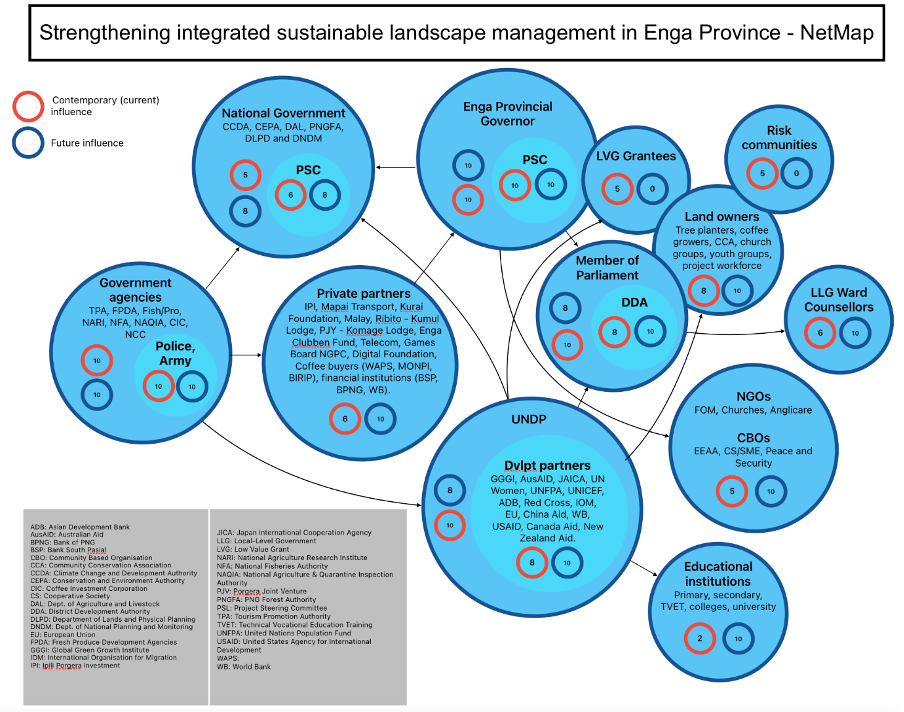

The first step in stakeholder engagement is to map who the stakeholders are. Farmers, cooperatives, local leaders, government agencies, private companies, and donors – all bring different priorities. But identification alone is not enough.

You identify who the stakeholders are, but it does not stop there. You need to move a step further by identifying what their role is in that given landscape, why they are interested, and how much they can influence things positively or negatively.

– Divine Foundjem

Stakeholders may seek livelihoods, resources, political influence or conservation outcomes. Their power can be enabling or obstructive.

Divine pointed to North Cameroon as an example: “We have in the north the effect of Boko Haram. These actors stop development partners from going to the field because they may easily be kidnapped. Those are powerful actors – but can you bring them to the table?”

Go beyond representation

Stakeholder engagement risks becoming a “checklist exercise” – inviting one farmer, one woman, or one minority representative to tick a box.

They say, ‘Okay, farmers are represented. The minority groups are represented.” But it’s just a checklist. They don’t really care whether that category of persons has the decision-making power to say things that they really want to say.

– Divine Foundjem

Real inclusivity means active participation:

Less powerful groups need empowerment to speak and relay messages back to their communities. Rapha cited the example of including informal loggers: “This inclusion is a long-term strategy. It is a process that requires tact and support. At first, these actors couldn’t even speak in front of the Director of Forests. As facilitators, we helped them build confidence, learn from others in the region, and engage in dialogue that led to changes in regulation.”

- Less powerful groups need capacity-building to speak and to carry messages back to their communities.

- More powerful actors need support to accept the participation of minorities and listen without feeling their authority is threatened.

As Valentina noted: “The important thing is that the powerful people have to listen. That is the most challenging – because sometimes they feel that by listening, they are losing their power.”

Balance law and legitimacy

Rapha reminded us that local realities often clash with formal law: “Most of the actors in the landscapes where we are working are local communities, operating informally in fishing, hunting or logging – and most of the time they are treated like criminals. In my perspective, they are not.”

He stressed the need to distinguish between legal, illegal, legitimate and illegitimate.

Sometimes the law doesn’t capture the local dynamic. Encroachment may be informal and illegal, but actually legitimate. That legitimacy organizes the way people intervene in the landscape.

– Rapha Tsanga

He cited an example of informal logging in the Congo Basin which illustrates how inclusion over time can shift dynamics: “For the government, informal logging was illegal. But we called it informal because we didn’t want to treat these actors as criminals. If they are not criminals, they can sit around the table, talk to the government, discuss regulations, and gradually operate legally.”

This nuance is crucial in designing multi-stakeholder fora where rules must balance conservation, livelihoods and legitimacy.

Acknowledge ‘difficult’ actors

What about groups that cannot be brought to the table – armed rebels, narco-traffickers, or criminal gangs?

“This is the elephant in the room,” Rapha said. “If we take them on board, we create conflict with the government. If we do not, we can’t implement ILM practices because they are the ones controlling the landscape.”

ILM projects can play a stabilizing role in violent conflict settings:

- In Burkina Faso, projects created social centres where young people play football or watch films, helping build trust and exchange information about external threats.

- In Colombia, initial stakeholder mapping omitted mention of armed groups – but facilitators used background knowledge to ensure their influence was acknowledged, even if they weren’t physically present.

- In Central African Republic, projects have worked indirectly through humanitarian organizations and the UN.

As Rapha emphasized, “ILM cannot solve all the problems, but at least it can maintain a kind of balance. Without ILM, the situation would probably be worse.”

Create alternatives for youth

Armed groups and war economies often attract young people with the promise of money and influence. ILM projects must therefore create livelihood alternatives.

Sometimes it is easier for a young person to join an armed group. When you have a weapon, you can get money. The idea is to create alternative activities, income-generating projects, so that they don’t have to join.

– Rapha Tsanga

This requires coalitions of actors – governments, donors, civil society – complementing project-level initiatives.

Co-create a shared vision

ILM can support the creation of a shared vision.

It’s important that those who sit together in a platform to manage a landscape develop a common vision of where they want to go. People come first. Landscapes are about human beings.

– Divine Foundjem

This vision cannot be forged in a single meeting. It is a long-term process of negotiation, adaptation and trust-building – but one that is essential for resilience.

Recognize the agency of ILM practitioners

The conversation then turned to the practitioners themselves. They are not neutral observers; they are facilitators, brokers, and often the only actors trusted enough to mediate.

Rapha recalled the emergence of forest certification in the Congo Basin nearly two decades ago: “The government allocated logging concessions on the map, everything was fine on paper. But logging companies had to deal with local communities who were hunting and fishing in the concessions. One of the solutions was to put in place multi-stakeholder platforms to discuss rights, what was legal, what was forbidden, and to adapt strategies iteratively when problems arose.”

He stressed that ILM practitioners have a critical role in organizing such processes at the landscape level, while also recognizing when to bring in state officials who ultimately hold policymaking authority.

Valentina underscored the importance of trust: “It’s important for practitioners to build trust so that all stakeholders recognize their facilitating role and so can genuinely broker dialogue.”

When people trust that the process can lead to change, even if it takes time, they are willing to sit at the table.

– Valentina Robiglio

Divine expanded: “In contexts of weak governance, farmers often don’t trust government officials to mediate conflicts. They believe officials can be corrupted by richer actors. That is where we, as practitioners, have to come in – to facilitate trust building, to guarantee trust, to create spaces where actors can see for themselves what is right and wrong.”

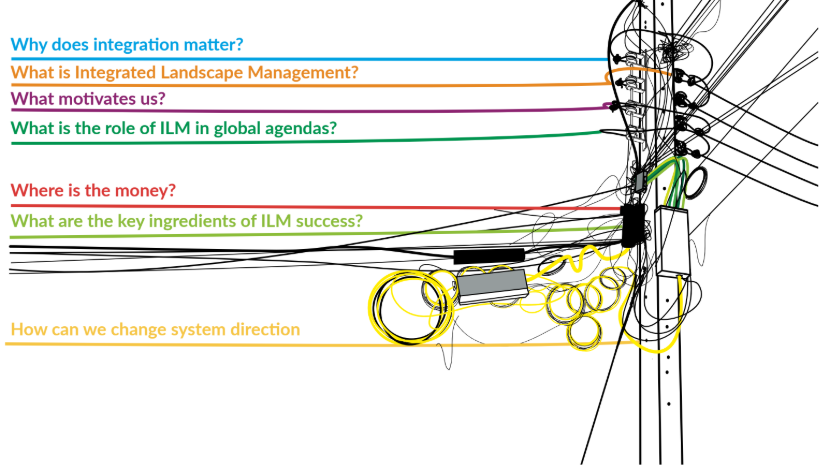

View multi-stakeholder platforms as processes, not events

Meetings are just one element in a much broader journey, as Valentina pointed out: “What’s important is to remember that multi-stakeholder platforms are not just about meetings. They are long-term processes – bilateral engagements, informal meetings, listening, and building enabling conditions. Meetings are just the visible tip of the iceberg.”

Rapha was clear about the proportion of effort required:

Ninety percent of the work is the invisible part – informal meetings, bilateral conversations, listening, understanding local dynamics. Only once that groundwork is done can you organize big meetings with nice pictures. Those are the visible end stage, but the real process is long, patient, invisible work.”

Rapha Tsanga

Invest in invisible work

Divine raised a challenge: “Donors often measure processes by the number of formal meetings held. But the groundwork – the informal meetings, negotiations, and mediation – is what really matters. It is resource-intensive, but it is what builds trust and makes change possible.”

Donors often complain about ‘transaction costs’. But really, transactions – the informal meetings, the shared meals, the building of trust and familiarity, the listening – are what results in successful ILM. Transaction costs shouldn’t be eschewed, but rather, invested in. High transaction costs are, in our view, an indicator of likely ILM success.”

Kim Geheb, Landscapes For Our Future Central Component Coordinator

Conclusion: stakeholder engagement is the backbone of ILM

Stakeholder engagement is not a technical step but the very backbone of Integrated Landscape Management. It requires patience, humility, courage and creativity – particularly in fragile and conflict-affected contexts.

As the examples from Cameroon, Burkina Faso, Colombia and the Congo Basin show, meaningful engagement not only builds governance but also contributes to peace, stability and resilience.

Through these insights, we’re continuing to refine and demonstrate ILM practice – showing that inclusive, negotiated and adaptive engagement is the path to sustainable and just landscapes.