For WCS Laos, the lead implementor on the Ecosystem conservation through integrated landscape management in Lao People’s Democratic Republic (ECILL) project, stakeholder engagement has proven to be the decisive factor in whether conservation efforts succeed or fail.

In the video below, Ben Swanepoel, a programme leader with WCS, gives us some insight into exactly what that looks like on the ground.

The communities themselves are going to be creating the success or failure of the protected area — not our good deeds inside the protected area.

Ben Swanepoel, a programme leader with WCS

From fragmented programmes to integration

WCS Laos has not always worked this way. Ben recalls earlier years when efforts were split into separate programmes: one focused on law enforcement, another on outreach, and still others on ecotourism. Each had merit, but their impact was limited.

“They had marginal success,” he reflects. “The only time we can actually demonstrate a genuine success — something we can measure — is when we put all of this together.”

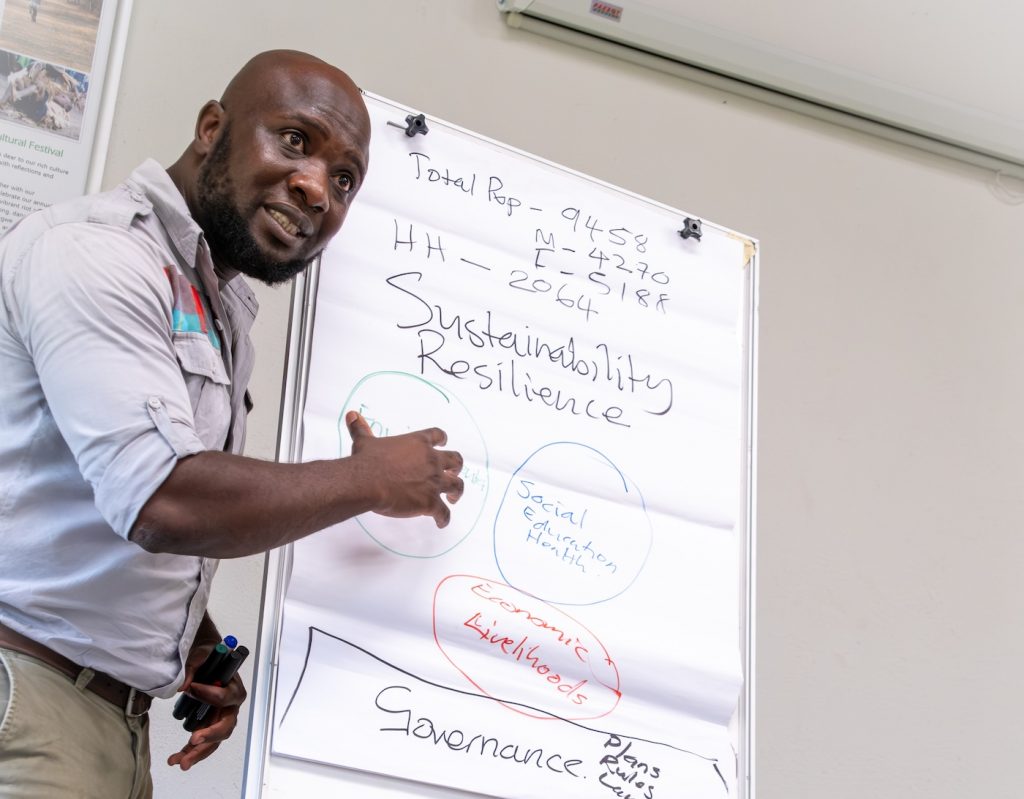

This insight has led to a new way of working. Now, conservation agreements are accompanied by multiple, interconnected teams: monitoring, livelihood development, stakeholder engagement, land-use planning, and integrated management. Together, they form a comprehensive strategy that addresses the complexity of the landscape.

Ben is convinced: “Integrated is just the right approach for a protected area like this.”

Shifting the balance of responsibility

What makes this integrated approach particularly powerful in Laos is the shift in who drives conservation success. In some contexts, conservation has been about fencing off land and keeping people out. In Ben’s experience, such models are not only unrealistic but counterproductive.

In contrast, the Laos project demonstrates that when communities are given a genuine stake in conservation — backed by economic opportunities, clear agreements, and accountability mechanisms — they become the decisive actors.

“It’s completely the other way around,” Ben says. “NEPL MU are actually going to the community and saying: how can we involve you in the conservation here? It’s the communities themselves that are going to create success.”

Coffee as a catalyst for change

One of the most striking examples comes from an initiative with five villages bordering a protected area. As part of the Ecosystem conservation through integrated landscape management in Lao People’s Democratic Republic (ECILL) project, with the leadership of the Nam Et–Phou Louey Management Unit (NEPL MU), WCS and its partners worked with 80 households to introduce coffee as a viable livelihood alternative. Coffee offered much higher returns and, importantly, it was linked directly to conservation agreements.

Households signing up to grow coffee also committed to refraining from hunting and other unsustainable activities. These agreements came with clear monitoring systems and penalties, ensuring accountability while offering tangible benefits.

“By doing that,” Ben explains, “the NEPL MU has signed conservation agreements. Everybody who wanted to do coffee has signed up, because they know they’ll earn more from this. And in return, they agree to stop hunting.”

This approach shows how carefully designed livelihood interventions can align community wellbeing with conservation objectives, creating a win–win scenario.

Lessons for Integrated Landscape Management

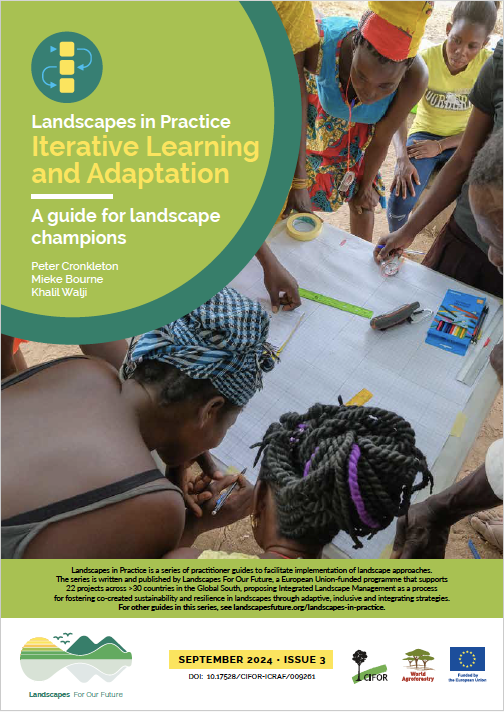

The experience in Laos offers valuable lessons for other projects in the Landscapes For Our Future programme and beyond:

- Livelihoods as leverage: Alternative income opportunities must be meaningful and profitable enough to motivate change. Coffee, in this case, provided a clear pathway.

- Agreements with accountability: Conservation commitments tied to real incentives — and backed by monitoring — strengthen trust while ensuring compliance.

- Integration over fragmentation: Conservation gains are maximised when law enforcement, outreach, livelihoods, and land-use planning are part of a single, coherent strategy.

- Communities as co-managers: True success comes when local people are not peripheral, but central, to the design and delivery of conservation outcomes.

These insights reinforce a central principle of integrated landscape management: sustainable change cannot be achieved through isolated interventions. It requires collaboration, alignment, and above all, a recognition that landscapes belong to the people who live within them.

As the WCS Laos experience shows, when communities see both the benefits and the responsibilities of conservation, they step forward not as passive recipients but as active stewards of the landscape. And it is in their hands that the future of these protected areas will be secured.