The Central Component is addressing key knowledge gaps in ILM thinking. The text that follows is based closely on Kim’s presentation at our SE Asian regional summit in Bangkok in late 2024, one of the first occasions in which he fully outlined this foundational perspective.

Let me start with a little bit of background about the Central Component’s role within the Landscapes For Our Future programme.

When I first started in my position as Coordinator of the Central Component, I was given 22 proposals. “Here they are. Read 10 kilos of paper.” What emerged very quickly from all of these proposals was that how the different projects across the world were implementing Integrated Landscape Management (ILM) was extremely diverse in terms of how they thought about it, and that presented us with a problem because, as a scientist, you’re trying to find consistencies. What you’re trying to see is that there is some strand across all of these projects that will allow us to say, “Yes, they’re practicing ILM.” That was very important for us strategically because we were supposed to be giving advice to them, but we had no standard against which we could then say, “All right, this is how ILM ought to be implemented, and this is how you guys are deviating, and let us help you with that.”

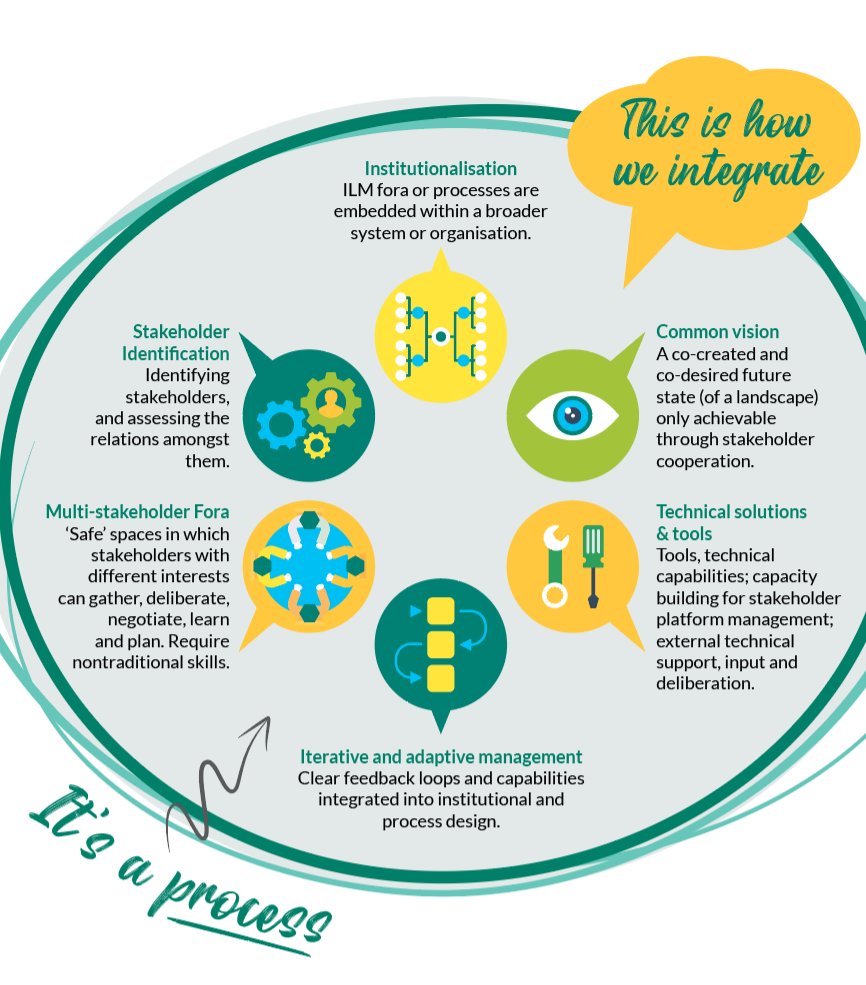

We didn’t actually have that, so what we evolved were these six dimensions or characteristics of ILM.

But that was a hypothetical, and it was our job then to work together with the 22 projects within the Landscapes For Our Future programme to disprove the hypothesis – that’s how the scientific process works. This presentation emerges out of that exercise and the disproving process, and then from visiting each one of the projects, learning how they think about ILM, learning how they’re implementing it and where it’s going.

One of the things that we are particularly concerned about, both within the projects themselves, but also more broadly when we think about ILM, is what I like to call “the inbetweenness of things”. After our learning missions together and our programme’s global and regional summits, we basically have a Community of Practice now. What constitutes the glue of that Practice? We’ve talked about trust a lot. And we talk about collaboration, which then requires a great deal of trust. We talk about cooperation. We talk about social dynamics. If we’re going to sum it all up, they’re social dynamics. And this is the glue. And it’s fundamental to successful ILM. Absolutely fundamental. Yet, the ways in which we develop or write about ILM does not really allow for us to use this kind of phrasing. Yet it’s critical to the success.

The other thing, because of this diversity amongst all of the projects, and because we’re researchers, is that we have to, of course, go to the literature. What can the literature tell us and what can support these emerging perspectives from within the 22 projects?

One key body of literature that has appeared is this area of systems.

What we’re going to do today is to think about ILM from a systemic perspective. Essentially, we’re going to talk about what systems are. Secondly, why we should focus on them. Why does it matter to use that kind of perspective? And then – and I’ll be explaining this when we get to that relevant section – how do we change system direction? Because that’s what we want to achieve. We judge the current direction to be wrong, bad, problematic, whatever it might be, and we want a change in direction.

But I will start with a quotation from a great French writer.

There is not much about landscapes in the classical literature. This one I found particularly powerful. Just as an amuse-bouche for the rest of the presentation.

So, what do we think a system is? What is a landscape?

When it comes to defining landscapes – and this was this was one of those things that we really spent a lot of time thinking about – they are complex. This is a key thing. We’re going to talk about complexity a lot more, but one of the things that was a key takeaway for us is that landscapes are already integrated. The physical unit that is the landscape is not the problem. Even if it’s very severely degraded, the degradation has occurred because it’s integrated. Because if we do this one thing over here, these other things happen. That is the integration we’re looking at.

They are social ecological systems: they emerge as a consequence of the relationship between humans and the environment within which they live.

And they are defined depending on purpose. When we talk about purpose here, what we’re talking about is “to what end are we looking at this landscape?” Why are we looking at it in this particular way? For WCS, you might look at the landscape because you’re concerned about ecology, so you use an ecological boundary. If we’re a government person, maybe we use a province or a district. For our plantation people, you might just see it as plantation. So there are different ways in which we can see. But one of the really key things is that they’re produced by dominant social, political and economic dynamics.

The geographers in the room are very comfortable with this idea that we produce our own environments. And this, of course, relates to, for example, all the conversations around planetary boundaries, all the conversations about the Anthropocene. We produce the new crust of the earth. There is recognition that we did this. We are responsible.

Let’s take that a step further to thinking about how do we then define Integrated Landscape Management?

It is a process (this is a very important aspect: it’s a means to an end) for fostering co-creation (this is also very important, especially within the context of multi-stakeholder platforms), for co-creating sustainability and resilience in landscapes through adaptive, inclusive and integrating strategies.

We’ve bashed this as much as we can and this is probably the best definition out there. Incidentally, the extent to which we look at the projects and the inconsistencies – not necessarily a bad thing – in how people think about Integrated Landscape Management also says a lot about this kind of work. This thinking about how we advance ILM is filling a very considerable knowledge gap.

We have to remember that integration has become this object that we understand… If we talk about Integrated Water Resources Management or Integrated Natural Resources Management, or the water-food-energy nexus, these are all approaches that are trying to obtain integration because we recognize that it is so, so serious. It’s incredibly serious being able to achieve this.

So let us go all the way back to, I think it was 1978. Those of you in my age group, you may remember that in those years, there was a publication that was understanding the systems[1], the interconnectivity between the elements in the system. That is what we’re interested in: the glue, the trust, the collaboration – these sort of non-tangible things that have to accompany any kind of process that we get involved in when we talk about systems.

The other thing that we want to draw attention to is that when you have all of these different elements, the nature of the relationships between them is insane. It’s not just Element A having a relationship with Element B. It’s not just that. Element A has five different types of relationships with Element B. Element B has relationships back to Element A. And then we’ve got 10 billion others. But when you fly above it and you see the systems begin to adapt to external and internal pressures, they begin to obtain characteristics that we can observe.

That’s why, for example, we can say there is such a thing as German society, and it’s distinct from French society, even though there are millions of different elements within it. We can observe it. We can see those differences between them. There is distinction.

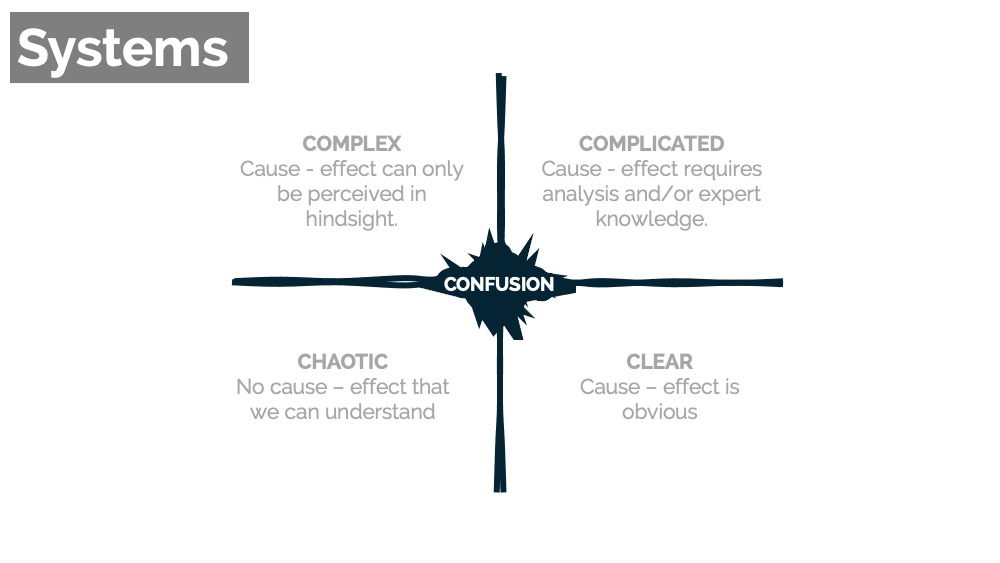

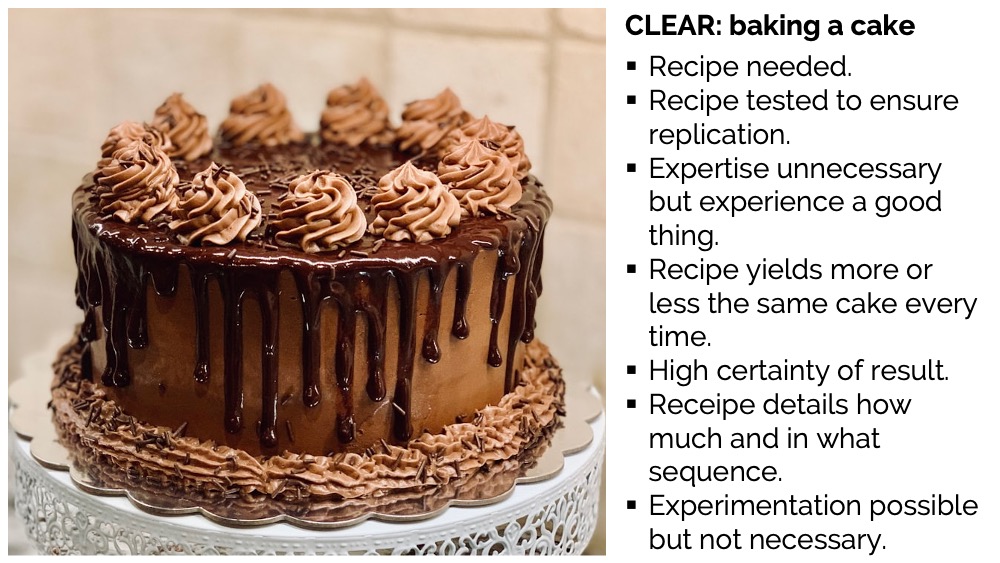

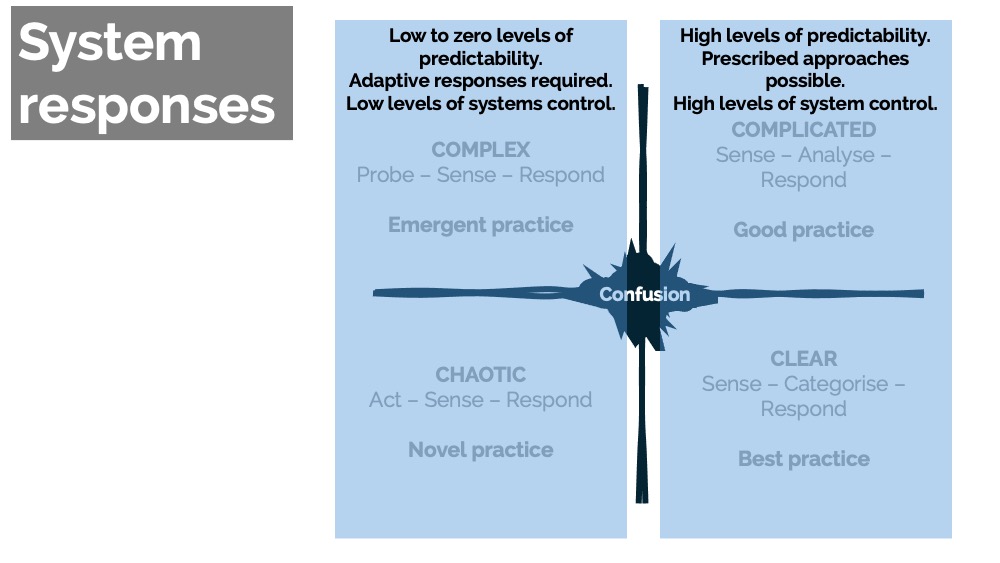

So we identified four different types of systems.[2] With simple systems, the Clear systems here, what we’re looking at is obvious cause and effect. If we do A, then B will happen.

So a great example of this is your cake recipe: you have the recipe, it’s tried and tested over time and, provided we follow the sequence and the ingredients that are stipulated in the recipe, more or less the same result will happen. (Until it’s me and I could burn the cake.) But that’s generally how it works. This is a very, very simple system.

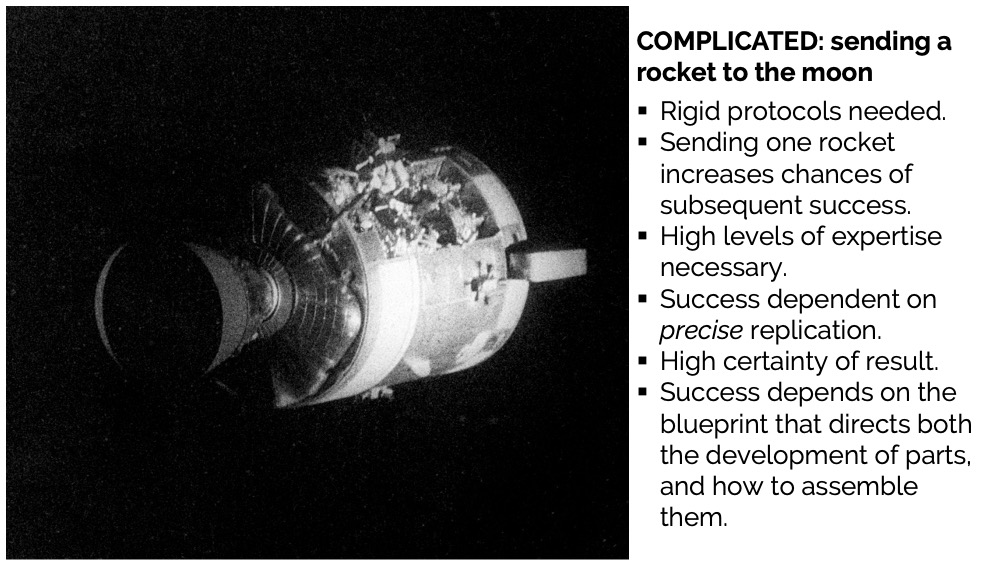

When we get Complicated, it’s very similar actually to a Clear system. However, here we require the key additional ingredient: expertise.

So sending a rocket to the moon is Complicated. Very complicated. Each one of those bits that goes into the rocket requires a particular set of expertise. It probably requires a double PhD in order to manufacture that bit and to understand how it all connects together – high levels of expertise.

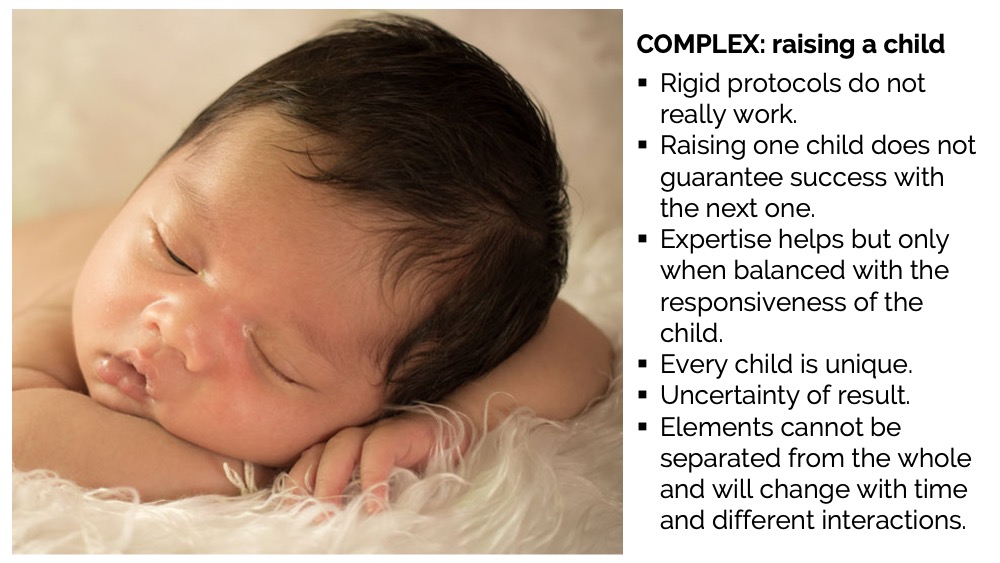

When we get to Complex systems, we’re talking about those 10 billion elements and all the different relations between them. This is very, very high complexity. There is causality in a Complex system, but we only see it in retrospect: something happens in the system – a disaster comes along – and we want to know why that disaster occurred, we look over our shoulder and we draw upon the time to explain. But in the moment, in the present, we’re not able to do that.

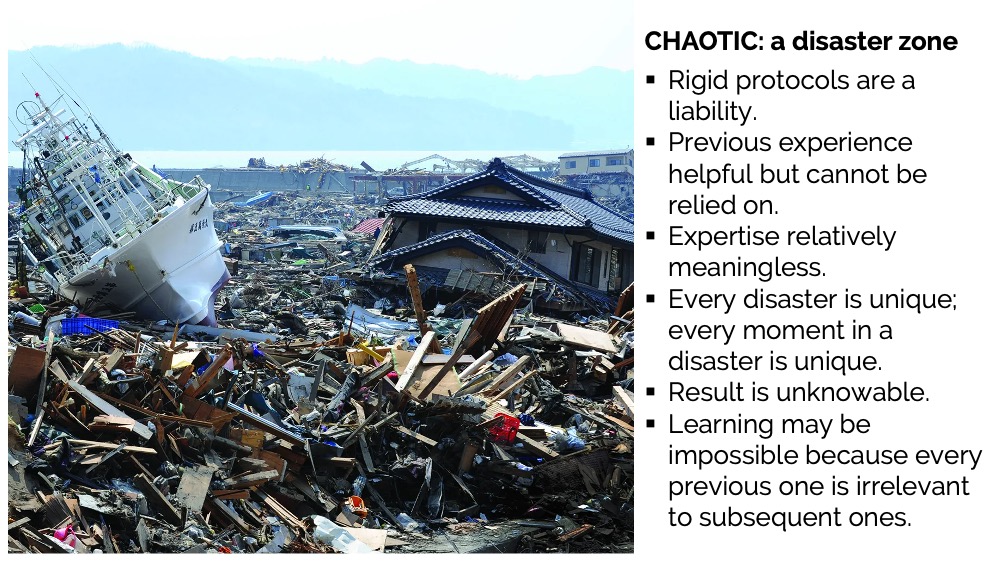

And then, finally, we have Chaotic systems. Chaotic systems are pretty rare, but highly pertinent to our discussions because of the concerns around our climate: if it tips over, then what will happen? We don’t know. And will it turn into a Chaotic system? If it turns Chaotic, we have serious problems. Very, very serious problems.

With each one of these, we have different levels of response. With Clear systems, we can use best practice. Good practice for Complicated. Emergent practice is what we require for Complex systems. For Chaotic, it’s novel practice – precedent has no meaning in a Chaotic system.

The two key takeaways from these different types of systems is that, on the right hand side, we have very high levels of predictability: we know what’s going to happen next. The result will nearly always be the same. We can use prescriptive approaches with those kinds of systems, and we have high levels of control.

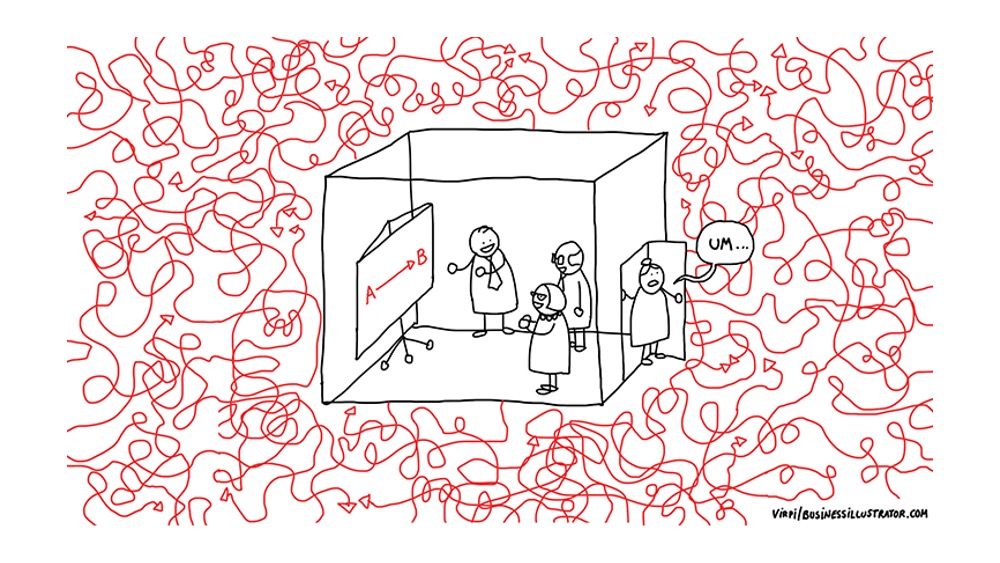

This is the opposite on the other side of the diagram. This is very important, because, as our definition of integrated landscapes indicated, landscapes are Complex systems. So when we take a management approach that is suitable for sending a rocket to the moon (a Complicated system), and then we try to apply it within this context (a Complex system), we’re bringing a knife to a gunfight. It doesn’t make sense. There is an inherent contradiction with that kind of approach, and yet we do it all the time. All the time. And this is what results:

This encapsulates that contradiction.

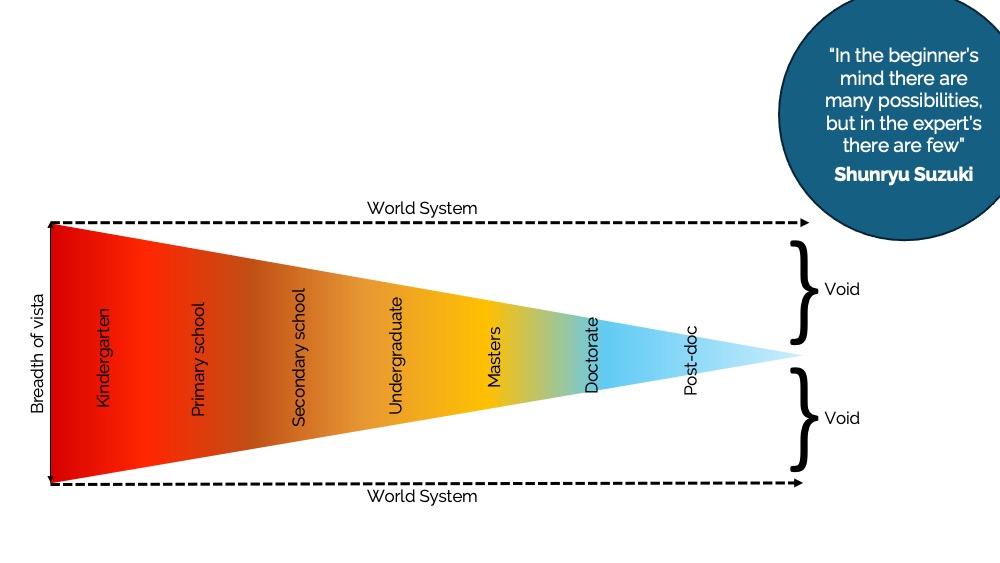

One of the reasons why this actually happens can be explained through the metaphor of a typical education progression. The breadth of our vista – that way in which we look at the world – at kindergarten level is completely non-specialized. Here the emphasis tends to be much more on behavioural aspects. Then, as we progress through it and we get to Post-doc, it’s very high levels of specialization. We support this culturally. “My daughter has a double PhD now,” somebody says, and everybody’s response is “Ooh, that’s amazing.” Well, maybe that’s much more of a reflection of the fact that she spent that amount of time with her education. Or maybe it’s a reflection of the fact that we spent so much money getting her there. However, another way of looking at it is that she’s also been taught to ignore other stuff.

So perhaps she is a particle physicist, and there is a bug ecologist here, and some urban geographers over there – all of these different specialities which emerge in how we try to address the world. But it’s the interconnections between them that counts. If we can’t see the big picture and we can’t see that elements from outside of our speciality are affecting the thing that we’re studying, then we have a problem. If I’m a social scientist and I don’t understand what that rock is contributing to social trends, I’m not seeing it. This then filters down into the ways in which we establish projects.

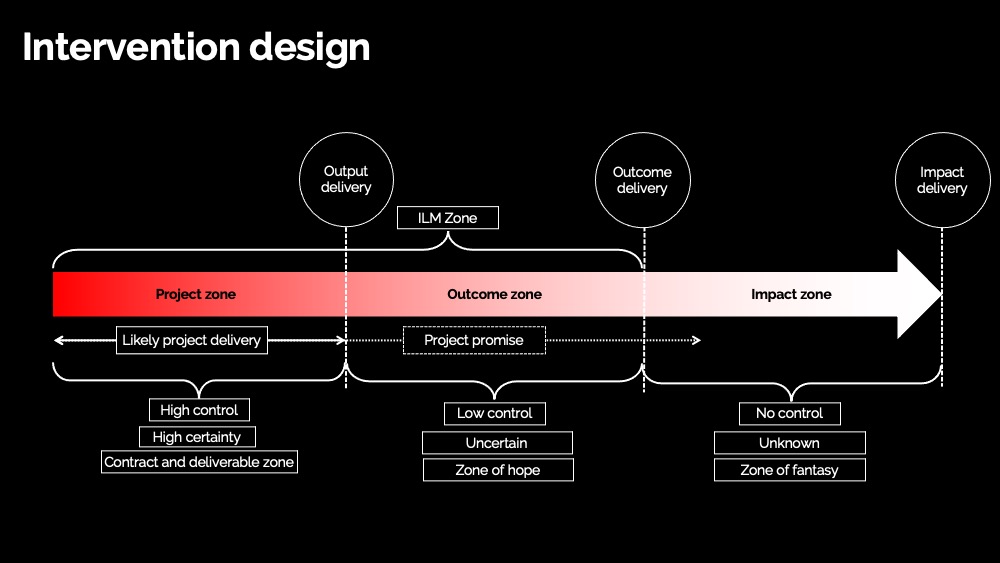

Typically, when you put together a proposal, the proposal template will ask you for three key things. The first is within the Project Zone, and here we have outputs being delivered: our deliverables. People often get incredibly preoccupied about those deliverables. Then we have our Outcome Zone with outcome delivery. We misuse the term ‘outcome’ all the time: outcome is a change in human behaviour. If you want sustainability of projects, the Outcome Zone is what you have to focus on, not the Project Zone. You have to shift your focus into the future with your hypotheticals and try. But you don’t get project sustainability just through output delivery.

And then finally, we have an Impact Zone, which is way down the road. There’s a huge temporal dimension to all of this, and this is so hypothetical as to be useless: it’s so far down the road. And yet we ask for it – that’s what project proposals want to see. But it’s pointless. Completely pointless.

The reason proposals are structured in this way in particular is around the control function: we want high levels of control. That’s a political statement. We want very high certainty too. And then, of course, we design our contracts against those things. We do not contract against things in the Outcome Zone because of the high levels of uncertainty there.

The Impact Zone is just the zone of fantasy. This is very important because we get compressed, generally speaking, and one of the things that violates against the ability to implement effective ILM is how we set up our project. If we want to change the world, and we want to move it into the Outcome Zone, then we need to revisit ways in which we set up our projects.

The other thing that I should emphasize here is that landscapes are socially produced. This is why it’s so important, because it doesn’t matter what problem we identify: when you look at the drivers that cause that problem to occur, we understand that somebody somewhere is doing something to cause that problem. And so a behavioural focus is necessary. What are we going to do to change those sets of practices?

I always go with Mike Tyson myself.

Again, a little bit of an amouse-bouche for what we move into. I actually also really like what Von Moltke has to say. I’m not a war historian or anything like that, but war is your Chaotic environment, right? And of course, what Von Moltke is talking about is that bring a plan into that kind of contest is laughable. But yet, we still do it. It gives us a sense of control.

But this should really be our inspiration:

Let’s take it from the leader of the Chinese Communist Party. He is entirely right. So we encounter a river; it’s foaming; let’s say it’s not too violent; maybe there’s a little sediment in it. We feel our way across. We’re using our feet and then we encounter a hole. What do we do? We back up. I think this metaphor is one of the best ones for good ILM practice.

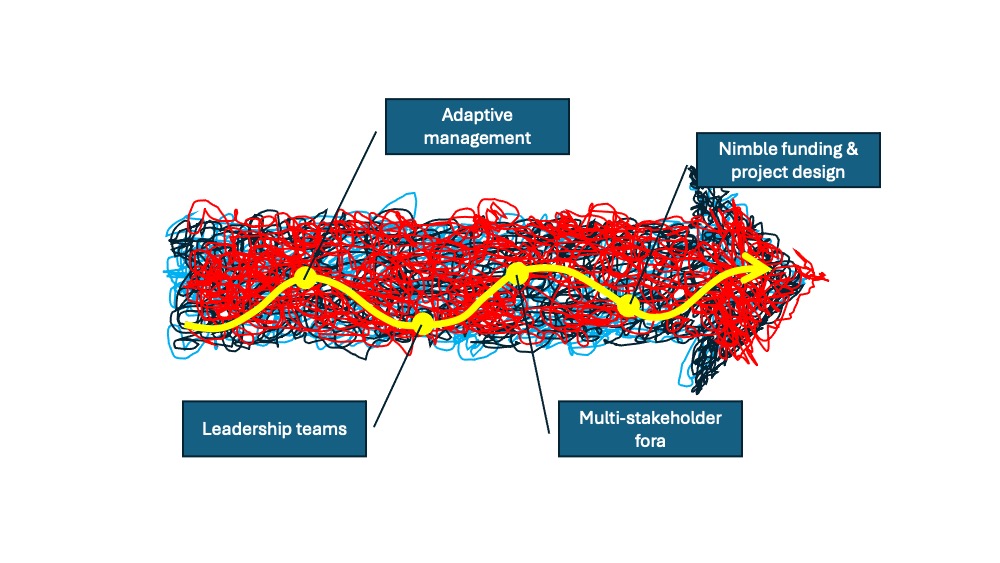

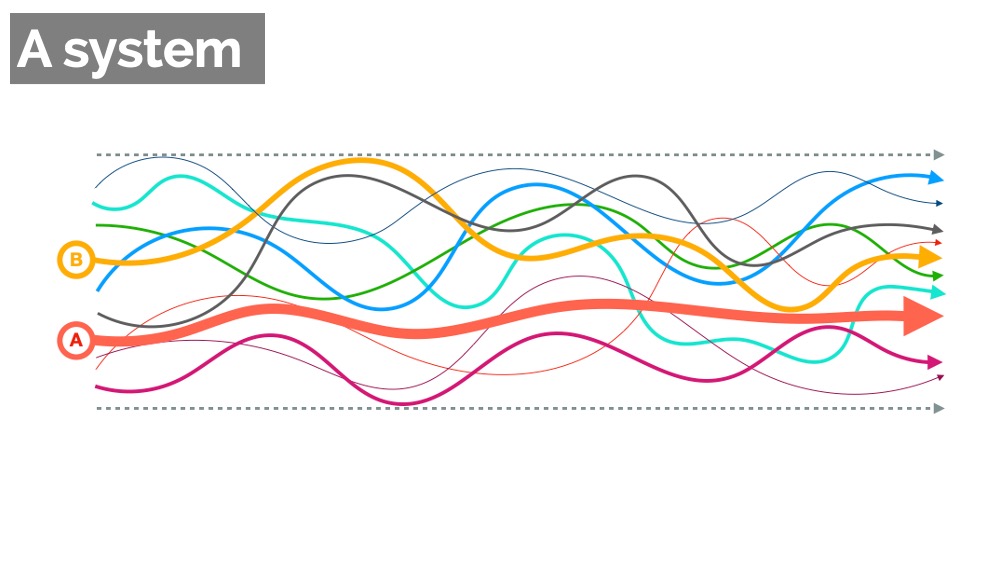

So here is our system. We call this the “hairy arrow” 😄. The scribbles are all of the processes happening within the system. Now, systems always have purpose: they’re designed to do particular things. It might be 25 things. We need to discover why it is – that’s part of the reason why systems really, really matter. But they also have direction. The directionality is a key point of how we are thinking about Integrated Landscape Management. The directionality of the system at its most basic is imposed by time: the system is progressing through time. So we have that movement happening.

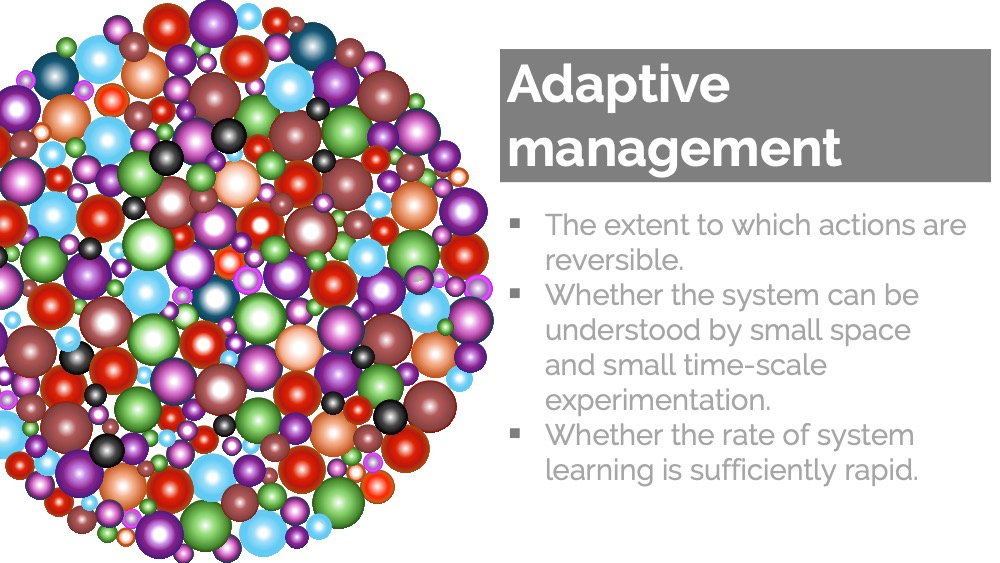

But there are also other things that motivate system directionality. There are four key things that we may need to unpack. I mentioned that with our six dimensions, the adaptive management remains a key focus for how we address Integrated Landscape Management. In Complex systems, adaptivity is the only way we can progress through. We have to be adaptive. That metaphor from the Chinese Communist Party is what we are thinking about: feeling our way but, in particular, reversing. Try this. It works. Progress. Try this. It doesn’t work. Reverse.

In our definition of adaptive management, they’re called small-time, small-step experimentation. You need to be cautious as well, because when you’re dealing in a social environment, you don’t want the consequences to obliterate everybody’s livelihoods. That’s not what you want to have achieved. So really this adaptive management and how we can conduct ourselves becomes incredibly important.

We talk about leadership teams. The leadership teams, of course, are also adaptive: as circumstances change, you might want to switch out people within the leadership team. The leadership is not the same as your administrative direction. This is also something we have a tendency to conflate: that because you have position power – for example, you are the country head of WCS in Laos – that doesn’t necessarily make you a leader. It’s a different thing. It’s a very different thing.

The corporate sector particularly understands this. They really get it. Leadership is much more about making sure that the people within your team accomplish the goals that they want to achieve. It has a great deal to do with delegation. Again, when we talk about control, that’s an issue. People don’t like delegating, especially when they made it to the top of the pile. You’ve become the minister; that means that you can tell other people what to do and you imagine that they’re going to do it. With joy. People who use their position power in order to force people to do particular things is different from delegating. Delegating is a transfer of power. That’s an enforcement. That’s different. Command is not delegation.

Actually, when you look at adaptive designs, delegation is this idea that “here is the alternative present that we want to achieve. How are we going to do it? Go off and think. Let’s come up with this.”

Everybody talks about the way in which Google organizes itself, which is all around team formation. They’ve created a physical space that they think is going to enable that to happen. They have divested themselves of rules, for example, that they don’t demand a dress code or mind if you bring a skateboard to work. They want you to be happy because they understand that happy people generally produce better results.

Back to the fuzzy arrow. There are three really key things here:

- The first of is the soft skills. For example, we have a conservation project, so we bring in a rhino specialist, a lizard specialist, etc. Very technical people. The next thing is how do we bring in the specialists who are able to weave or enable a Community of Practice? That is a serious skill. I can’t do it. I know what I can’t do, and that’s one of them. It’s also one of the reasons that I’m very good at delegating: because I know just how limited my skillset is. I don’t have a problem with that: there are plenty of people who do things far better than I can and they should be doing those things.

Soft skills include – and these are absolutely essential: facilitation, mediation, negotiation. Those are the three key things that we’re looking for and which should be populating projects if we want to yield the outcomes that we seek. - The second thing is the idea of convening. It’s the idea of assembly. We assemble people: when projects go into an ILM arena, they assemble the stakeholders. That process is fairly self-evident. But we also talk about convening knowledge. There are two aspects to convening, and that really matters.

As technical people, we have a particular type of knowledge. In the world view of Indigenous people, their Indigenous knowledge is way more important than our type of knowledge. It’s what they use day to day. That’s really important to understand. So we want to be able to obtain a mixing between the two. And in terms of bringing new knowledge to bear, whether it be their knowledge or our knowledge, whether it be just the knowledge that this person holds vis-a-vis the knowledge that I hold, it is the mixing together of those knowledges that can very often trigger a better approach. This becomes incredibly important: this thinking about precisely that. - And then there’s the whole idea of risk sharing. This risk sharing thing is really controversial. However, if you go into a rural community environment and you’re saying, “OK, we’re here and we’re going to transform your livelihoods. That’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to transform you guys. You’re going to be so happy by the time we’ve left,” and then you stand back. Technical people do that. We’re trained to not engage to a full extent. We’re trained to be “unbiased”. We have to separate ourselves from the object of our study – that’s the basic idea. It’s very inherent in the technical context. We structure all of our surveys in that particular way. That might be possible when you’re looking at stones, when you’re looking at bugs or something like that, but it’s a lot more difficult with people. And risk sharing implies that, for example, we bring to the table networks. We bring to the table people that we can actually talk to. So then when we identify community problems, then we can take it up the ladder. We can be messengers. That’s a very simple one.

But other people get much more stuck into the whole advocacy thing. The reason a lot of technical people don’t like the idea of risk sharing is because it implies advocacy, and advocacy is not what technical people do. Except for every single climate scientist on Earth.

We retain within our new kind of model multi-stakeholder fora, and this is where the integration happens. This is where we bring it all together. And really, integration in many respects can be seen as a mixing of knowledges and a mixing of experiences. But this is where it comes together.

One of the things that we also struggled a lot about is the idea of decision-making within multi-stakeholder fora. All too often we see projects where they say, “We established a multi-stakeholder platform” and it’s more of a consultation: “we stood there and we told them what we were going to do.” This is very common, especially with big development interventions. We go there and tell the villagers, “We’re going to build this huge dam in your neighbourhood. You’ll be adequately compensated.” Then we leave.

Let me offer you a metaphor. One of the world’s largest dams is the Itaipú Dam, which sits on the border between Paraguay and Brazil. There’s this great anecdote from the “public consultations” that were happening there. The dam officials were going from community to community to community and doing exactly this, right? This idea of “We’re telling you what we’re going to do; we expect you not to complain,” that’s implicit in so many of these initiatives. One of the dam officials stood up in a room full of Indigenous people and, in some exasperation, said, “If you want to make an omelette, you have to break some eggs.” And then one of the Indigenous community stood up and said, “Yes, but it’s our eggs and your omelette.”

So the idea of decision-making, especially with big projects like that, which have strategic relevance to economies, whole nations, national pride, that kind of thing… The idea of delegating decision-making powers down to community levels, a mixture of different types of knowledges, is very controversial a lot of the time.

From that, we emerge our new project strategies. How are we going to take those incremental steps forward, feeling with our feet, reversing when it doesn’t work, whatever? All of these are small hypotheses that we develop as we implement. “This might work. It seems plausible.” We try it; it doesn’t work. We reconvene; try again.

What’s amazing about a lot of this stuff is that we do this all the time, but we just don’t want it in our professional lives. We do this in our families when we have a debt problem or somebody crashed the car or we’ve got big bills to pay. “What are we going to do? How are we going to pay for that?” We do this all the time, but we don’t want to bring these kinds of things into our professional lives, for whatever reason.

The other thing is this whole idea of co-creation. As we advance forwards and we’re talking about these kinds of things, co-creation is one of the most magnificent ways in which you can empower. Once again, it is delegation. You’re saying “you have responsibilities; you have a say in this.” It’s not rhetorical. We need to be a lot more sincere about our messaging.

What breaks trust? Often it isn’t just a cleaver. It’s not just a sword that we bang down on the table and suddenly trust evaporates. Often you lose trust incrementally – that’s part of the difficulty. We have the tendency to bifurcate absolutely everything: right, wrong; black, white; all the way down, and yet we exist in between those extremes all the time. And we forget our language demands that we don’t see our everyday, our normalcy, in those particular ways.

Finally, nimble funding and project design. How do we actually create project templates and designs that better address the outcomes that we’re trying to achieve? This goes all the way back. We spool backwards to the idea that a project design that is designed for Simple or Complicated systems, doesn’t work in a Complex one. Yet we all say that we want to change the world.

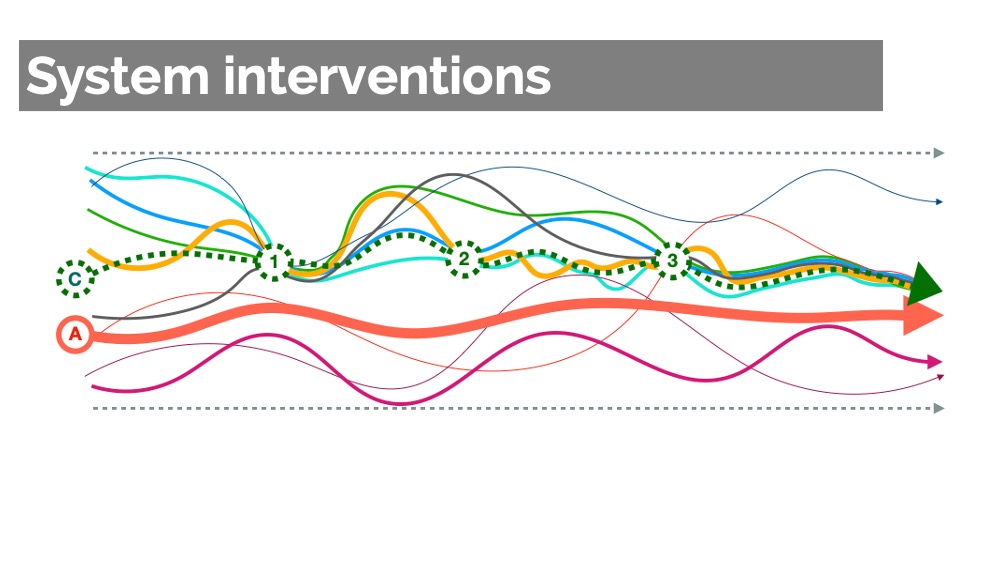

So this represents a system. Here we have all these different elements going around like that. The dotted lines are our system boundary, however we want to define that – we always have to define the boundaries. Let us imagine that these are all people. They’re progressing through the system. One of the things that we pay very little attention to is that every time they interact, every time they encounter another element moving through the system, there is a tiny change. There is a tiny, tiny change.

Complex adaptive systems are systems that organize themselves in particular – I’m going to use the word – directions. Now, it might not be the reason that one actor within the system wants. It is the merging of those different interests that then provide the system with its overall character and directionality. What I’m saying here is that for Actor A, its purpose influences system directionality more than the other individual actors.

We judge that the direction of this particular system is not where we want it to go. That then becomes the raison d’être – the purpose – of our proposal, and we design an intervention to get into the system. What our intervention (the dotted line) does is it implements a multi-stakeholder forum, and it invites Actor A to come to the multi-stakeholder forum. But actor A, because Actor A derives its power outside – it’s exploiting scale here; it gets its power from the government – it sees no reason why it should join the multi-stakeholder platform. However, we have to make representation to Actor A. We have to think about it. What Actors C does – the intervention – is that it implements that event and all of these different actors come in and they become changed a little bit as a consequence of that event. We bring to bear our soft skills, we bring to bear our convening skills, we bring to bear the knowledge that we want to share; and it’s a two-way process between us and them. They become changed a little bit.

Then we hold another event, but some of those actors go off and do their own thing; they don’t want to join us. Some of them do come and what happens at that moment then is that the ones that did show up become changed a little bit more, and they go out and they talk to the other actors that didn’t show up for event number two. And they persuade them to come to event number three. And the point being is that through this sequencing, as we progress through time, we begin to establish a competing agency within the context of the system. It begins to compete with Actor A. The point here is that actor A is pushing the system in one particular direction. Now, because of these activities, the collaboration that emerges between Actors D, E, F, G and H begins to shift the system in a different direction.

It doesn’t shift it in the best possible direction. It’s not going to be the direction that you want, but it shifts it towards that. It’s really fundamental to working within a Complex system: you don’t get what you want. That’s part of the reason why in our proposals and in our funding processes, that level of ambiguity should be acceptable.

These events, these moments in the implementation process, they are guaranteed. These are things that we can say that we can promise within the context of our proposal. “This event was held.” It’s an output. How we run those events is absolutely critical to our being successful within that project.

However, promising an outcome is not possible to do. That’s true of agents within the system as a whole, and it’s true of the system as a whole. Maybe, and we don’t know, but maybe, because the implementors of the system keep watching what Actor A is up to, then when Actor A sees that the system is heading in the direction that they’d rather it didn’t go in, then they join. Maybe, but we don’t know. There’s a lot of unknowns. The point becomes one of trying and heading in that direction, experimenting with it, and again, we revert back to the adage: We try; it works; we progress. We fail; we reverse; try again.

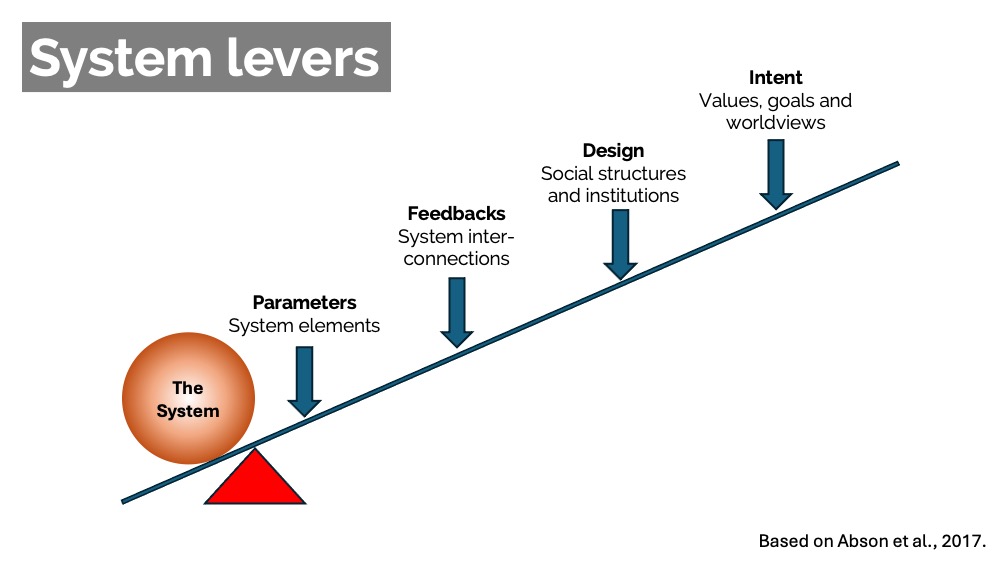

Abson, D.J., Fischer, D.J., Leventon, J. et al. 2017. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46(1): 30-39, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y

Okay. A lever. Where best to push?

Going back to Donella Meadows. She advocates that we have to identify or understand our interventions and systems in terms of levers. She came up with 16 different interventions. These guys here[3] have conveniently organized these into four broad areas.

The Parameters area is where we typically locate our policy. This is where regulations, government interventions, and so on typically occur. They tend to be small time, and they address an immediate problem, not necessarily a long-term societal issue. We know that a lot of what governments actually deal with (for example, “How are we going to address the climate crisis?”) is small scale, time tight because they don’t want to get too ambitious; they don’t want to disturb the order of power. They don’t want to disturb their control system – that’s their particular strategic interest.

The Parameters area focusses on system elements rather than the relationship between them. Feedbacks is the system interconnections, which is another area where intervention can occur. Of course, as we progress further outwards on the lever, we’re getting greater strength being delivered into the stick, so to speak. So then we get into the really promising areas: Design, focusing on institutional change, and finally Intent, focused on behavioural change.

Parameters, to use our temporal metaphor, are your quick fixes. Intent is systemic fixes; these take more time.

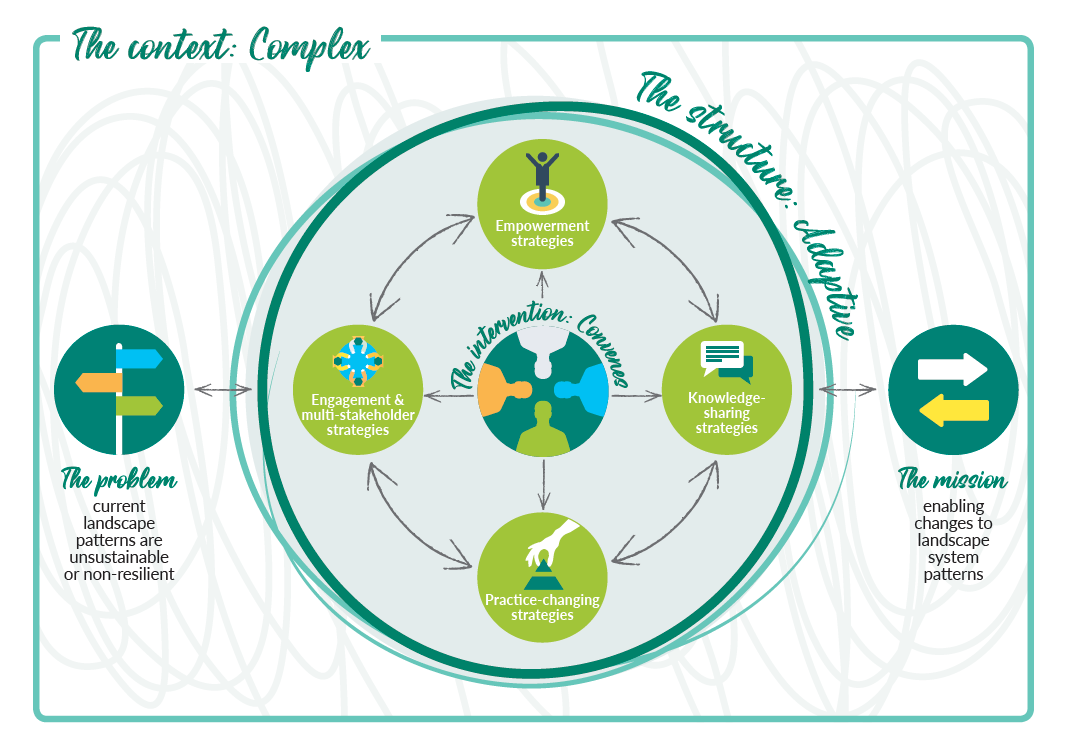

And so where we have gone with all of this is an overall design of thinking about how we can position Integrated Landscape Management. We phrase it in systemic terms: the system is heading in the wrong direction. What we want to do – our mission – is that we want to change system direction.

We understand from the outset that our context is complex, and we will evolve our strategies because we are adaptive – that is our implementation structure. And in the middle of this, the key function of the intervention is to convene people and knowledge. Those are the two key things, we think. (We may be wrong.) And we use our strategies – the ones that I’ve already touched on: nimble-footed funding, multi-stakeholder fora and leadership teams.

Here is, if it’s not an amouse-bouche, a digestif, to finish.

[1] Meadows, D. 2009. Systems thinking: a primer. London: Earthscan.

[2] The Cynefin Framework, based on the work of Dave Snowden, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N7oz366X0-8. See also Snowden, D., Greenberg, R. and Bertsch, B. (eds) 2021. Cynefin: weaving sense-making into the fabric of our world. Colwyn Bay: Cognitive Edge – the Cynefin Co.

[3] Abson, D.J., Fischer, D.J., Leventon, J. et al. 2017. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 46(1): 30-39, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-016-0800-y