Why were we playing “broken telephone”? To illustrate what invariably ends of up happening when we put the facts about our worthy projects out into the world. In our marketing and communications, we tend to detail the fancy name of our project, and who its funders are, and we list the many impressive outputs we intend to produce… We use technical jargon and scientific language. But does the meaning carry across? Do we inspire people to tell our stories? And when they do, what information do they convey to the next and the next and the next listeners?

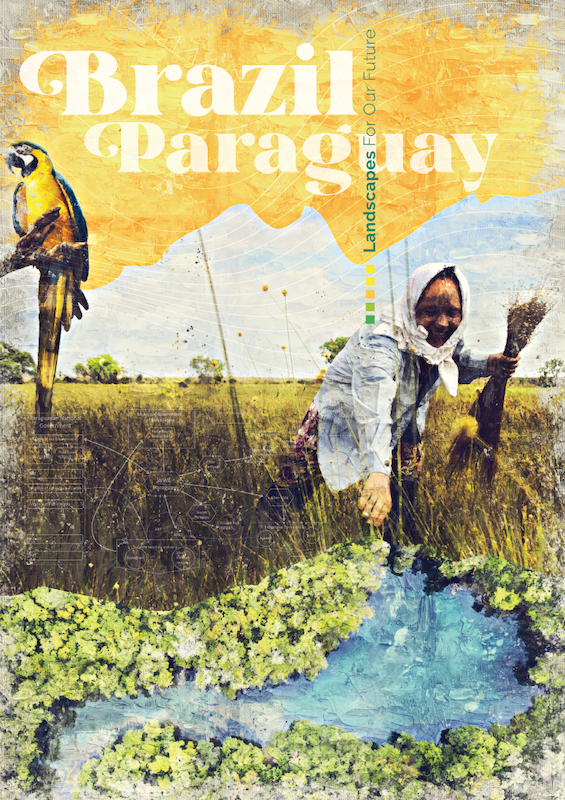

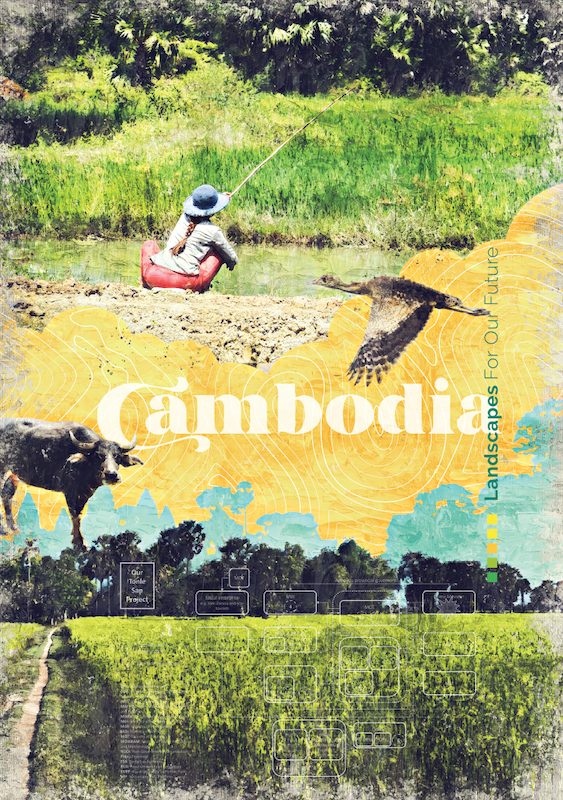

Participants at our communications workshop were challenged to tell a story about their landscape. Something that would hold listeners’ attention and capture their imaginations. Our location was an art gallery. As props, all they had was an art piece we had collaborated on. No PowerPoint, no text, just artful storytelling.

The results were magical! It turns out we have so many talented storytellers amongst us. Here are two of our favourites.

“Do you like my purse?”

Patricia Roche from our Cerrado Biome project in Brazil and Paraguay captured our attention with a question (and a sneaky little prop). The stylish, gold-hued bag over her shoulder, she explained, was made from golden grass in the landscape her project is working to protect.

“If you think about South America, I guess that you might think about the Amazon, right? But the Amazon is not the only important place in this whole continent. We have one that has five percent of the biodiversity of the world. Called the Cerrado, it is shared between Brazil and Paraguay. So now I’m representing the two countries, and we are working together to make people understand that this ecoregion exists, and that it is important.

“And what you can see here (she points to the picture of the woman collecting grass) is that it is not only important for the livelihoods of the people, but if you look here (she sweeps her hand across the horizon on the art poster) you will see that there are not a lot of big trees, right?

“We are working to make people understand that the grasslands and the savannahs are also important. They are natural ecosystems that may not have a lot of trees, but have a lot of importance.”

“The richness of this eco-region is beneath. It is the water that it gives to the rest of the region of South America. So the water that I drink in Asunción, the capital of Paraguay, has a lot to with what the Cerrado provides.

patricia roche

“Close your eyes and I’ll tell you my dream”

Keo Samnang, from the Our Tonle Sap project in Cambodia, took an unexpected turn with his storytelling. Initially concerned about how to present his project without the use of PowerPoint, he aced his presentation by appealing to our imaginations as he had us imagine a father and son and the fate of the fish-filled landscape that was their home and source of livelihood.

“Imagine 50 years ago: the Tonle Sap region is rich in fish. One day a family – dad and son – go into the river by boat. It’s very rich in fish. The fish bite and are brought into the boat.

That’s where the dream turns to a nightmare: enter the infamous Khmer Rouge: “After that, as you know, Cambodia has a war. So people are not allowed to go fishing. After about 10 years, the war is finished but the people have lost everything…” Samnang explains the downward spiral in which the government brought in revenue by leasing the land to the private sector, who depleted the natural resources further and further.

“One day, the people – the father and the son – go to the river to catch the fish, but they cannot get more fish. So they call for help to sustain their natural resources. The government and the funders and the NGOs come together to support them by creating a protected area and a community fishery for sustainable use. And at the same time, they also support livelihood activities by providing the poor with buffaloes, as well as technical expertise on rice growing and eco-tourism.

“So the tourists come, foreigners come, and the money is used for community development, construction of toilets and school material supplies.

And 20 years later, everyone has a surprise: the fish are still alive and the trees are still alive. As for the people living in the area: their livelihoods are better and the tourists come from day to day. We have a green landscape with rich biodiversity and the people are happy.

Keo Samnang

Every poster tells a story.

Keep your eye on our social media for more highlights and the tales behind these. 😊