When our Central Component gathered in Northern Kenya recently for a team workshop, there were fascinating conversations to be had. One dawn morning, Valentina Robiglio grabbed a coffee and sat down with her colleagues Kim Geheb and Peter Cronkleton for a discussion on a topic that rears its head all the time but is very rarely addressed directly.

Valentina: So, in these past days we have talked a lot about ILM, landscape management and landscape approaches, and we talked about the six elements that are important for ILM, but we haven’t really touched on an underlying element that we know is very important, that is power. Can you tell us more?

Kim: Landscapes are socially produced. They emerge as a consequence of human activity and human relations. And, of course, within human relations, power is a powerful characteristic of the relationships between people. And so we understand that power finds its way into our understanding of landscapes. In fact, I often suspect that power – and the power relations between stakeholders within a landscape – defines the landscape. It’s a very dominant characteristic of how landscapes look, their condition and how, ultimately, they’re governed and managed.

In fact, I often suspect that power – and the power relations between stakeholders within a landscape – defines the landscape. It’s a very dominant characteristic of how landscapes look, their condition and how, ultimately, they’re governed and managed.

Kim Geheb

Valentina: So, when you think of power in this way, then at the relationship that stakeholders might have through formal and informal institutions, is there a way to regulate or influence power relationships in a landscape in order to achieve the outcome?

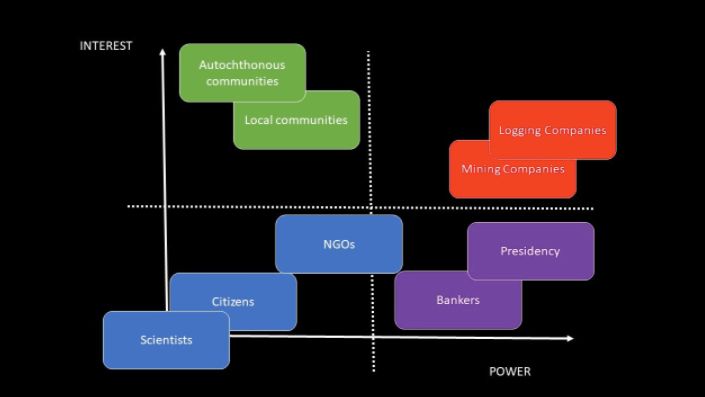

Kim: We very rarely like to talk about power. It’s kind of a dirty word and yet it’s such a prominent feature of how we can actually characterize a landscape. I think that a lot of the approaches that we use within the context of ILM are implicitly about managing power relations. For example, we talk about inclusivity. That’s because we recognize that there’s a group of people within the landscape who are not included in the power landscape. So we try to manage that. When we use multi-stakeholder fora, for example, that’s also another way we try to ensure that power is better distributed amongst participants in a landscape. Very often the kinds of capacity building that we provide are intended to empower people”.

We very rarely like to talk about power. It’s kind of a dirty word and yet it’s such a prominent feature of how we can actually characterize a landscape.

Kim Geheb

Peter: I think you made a good point the other day when you were talking about proponents of ILM projects, whether they’re NGOs or other types of actor: they are not conscious of their own power and so they don’t see their ability to convene people, their ability to interact with people at different levels of power within a landscape. They underestimate how important power is because they’re coming in as a powerful actor in a landscape. And so I think it was a good point when we were talking about not being more conscious of the power dynamics, and how an external facilitator plays into that dynamic, but being conscious of themselves as a broker, they’re trying to bridge these gulfs between different people, realizing that when they’re out of the system, things could necessarily snap back into their original form. So, they need to take that into account: how do you change power dynamics and not put people in jeopardy, not create conflicts, not create other types of problems that were unintended at the start.

Kim: Spot on. So we think that when it comes to project formulation, a really critical part is how we understand our intervention. I mean, even the word “intervention” has power connotations, and so our intervention into a landscape has to be accompanied by a critical self-reflection of our power as technical people, as highly educated people, as people who potentially come from other cultures: how that’s going to influence power dynamics within a landscape. That becomes really very, very critical.

Valentina: I was thinking, we are now talking about power in general, but then it’s power to do what? And maybe, based on your experience and on the initiatives that we are looking at in the project, could you give some examples? I mean, what are the key dimensions of power and the key elements of power, and to do what, that count in a landscape when we talk about multi stakeholders?

Kim: I mean there’s a hard line, of course, with power. And so for a lot of our landscapes, we have to deal with violent conflict, which is kind of like the ultimate form of oppressive power. We see this in, for example, our Papua New Guinea landscape. We see this in our Burkina Faso landscape. The landscape that we share between Chad and the Central African Republic also. This is a key aspect of trying to implement ILM in these contexts. So that’s one part of it. But I also think that, when we talk about ILM, we have to really draw attention to is that the first word in ILM is ‘integration,’ which I think is very much a power statement. Often, the highest form of integration is collaboration, but there are powerful actors that prevent collaboration and get in the way of collaboration, and so power then becomes a significant facet that we have to pay attention to if we want integration. That then becomes central to our thinking about how we engage with stakeholders and the governance systems that then emerge out of that collaboration.

The first word of ILM is ‘integration’, and I think that integration is very much a power statement.

Kim Geheb

Peter: It’s also important to think about the sources of power. So, you might have people that are economically powerful. You have political power. There are other kinds of social power that give people rights and obligations within a landscape that influence how people interact. There are formal sources of power and informal sources of power, customary rules, traditions that shape how people are working. But also, in some of the landscapes we’re working in where there are illicit activities, the issue is actually the lack of power of some key stakeholders. Maybe you’re in a frontier area where governments don’t have a strong presence and because of that, for example, cross border drug trafficking influences how people interact in a landscape. It could either be that the government is absent, so these actors are in the landscape, or they’ve been co-opted somehow and that the power comes not just from the economic power of these illicit actors but also the threat of violence. And so, you have to be aware when you’re working in these landscapes that you’re not putting people in jeopardy when you leave because you’ve encouraged them to exert their rights or to stand their ground.

Valentina: I think this is very important because often we have the perception or there is this assumption that when you talk about the state or ‘el estado’ there is power. But actually, in our analysis, often it is the fragility of the state that generates and often the public authors can generate it. So it’s very interesting. And then what is the power that ILM practitioners have? So when they start intervening in a landscape, engaging with stakeholders, of course they come from an institution with a name, but what is the type of power that they have to exert? The type of power they have when they start and the type of power they have to assert in order to build that constructive dynamic. What do you think? How would you describe that problem?

Kim: I think it’s profound, and an intervention has to be self-aware of the power that they bring to a landscape, because it’s basically a power landscape. Fundamentally, when we talk about an ILM success story, it’s because power relations between actors have been reconfigured in positive ways. And so a lot of the power that an intervention can bring in an ILM context is, for example, as Peter mentioned, convening power: the ability to assemble actors within the landscape. I think we often underestimate how difficult collaboration is to achieve, but our ability as an intervention to ‘weave’ collaboration has high potential. For example, if we bring into the equation mediators, or we bring into the equation facilitators – people who have the soft skills to enable or facilitate people to come together – this then becomes very important.

I also think that the power of voice is something that we pay very little attention to. A key characteristic of multi-stakeholder platforms is the emergence of voice. It is that people feel emboldened and sufficiently confident that they can say and speak out about the problems that they confront within the landscapes. Very often the kinds of things that they talk about are significant power imbalances within the landscape. So, hypothetically, let’s say we have a landscape where there’s a very large corporate actor. That immediately changes the power dynamic. It’s a massive presence that comes in, and so an intervention might have the resources to diminish that power, or to draw that actor into the landscape arrangement. To change this, the intervention might be able to take advantage of its own relationships with government for example. This is a very key thing: that a lot of interventions have these networks that local people don’t actually have. We also have to understand that at higher scales there are all kinds of power dynamics; that we might have NGOs that are disempowered vis-a-vis the state or the government. Peter touched on a very good point: that a lot of the contexts where we operate are under-regulated and the presence of the state is very low, so we’ve got a hole. In fact, it can potentially get meaningless to talk about formal power within these contexts. Everything is informal and that creates its own dynamic. As an intervention, we have a phenomenal ability to alter the power dynamic, and figuring out how we can do that means that we have to look squarely at power: how we can characterize it, understanding its dynamics and how it flows across the landscape, how it influences the landscape. Then we can position ourselves in such a way that we can change those dynamics in positive directions.

Peter: And one way we do that is we’re very conscious of the need to come in as neutral actors, or try to. You will hear the term ‘honest broker’: when we come in we’re able to go and talk to the owner of a timber company or visit a rancher and talk to them, whereas an environmental NGO may have difficulty building bridges with those actors because their environmental agenda is seen as a threat to the livelihoods of these other actors.

Often, we go in with a conservation agenda ourselves, but we try to put that in the background and come in with a message that in most landscapes there are opportunities to find common ground, common interests. You don’t necessarily have to focus directly on the main conflicts but you can find lots of other dynamics that can be fixed or resolved through negotiation, because people generally on all sides have interests in things like clean water, people like to avoid pollution where they live, obviously people want to avoid threats of violence… So there are opportunities.

Peter Conkleton

Valentina: I was going to ask about the power of an ILM practitioner. It is very much related to the capacity of the practitioner: the skill to convene, to build trust, power that comes from accountability and also the capacity to identify this ‘neutral space’, to be perceived as an owner. I think that’s very important, but then there might be a challenge when there are issues related to conflict, conservation, development… Very often we have very strong conservation institutions that come in managing the landscape, and maybe they already have a legacy and they have an agenda that’s very clear, so does that reduce their convening power as an ILM practitioner? Or what do they have to do in order to be perceived as more neutral and more able to really work across the different dimensions?

Very often we have very strong conservation institutions that come in managing the landscape, and maybe they already have a legacy and they have an agenda that’s very clear, so does that reduce their convening power as an ILM practitioner? Or what do they have to do in order to be perceived as more neutral and more able to really work across the different dimensions?

Valentina Robiglio

Peter: You sometimes hear people talk about fortress conservation: where it’s very top down, very much a command and control approach to conservation. And many environmental NGOs and governments have confronted the issue that they create enemies among local actors. The people that they need to convince that conservation, certain types of biodiversity or conservation of different landscapes is important, are seen as a threat by the government and those people see the technicians or employees of an NGO as threats. So you’ve seen a shift over recent decades to strategies like co-management where environmentalists try to identify sustainable livelihood options or alternatives that local people could still make a living, still feed their families, still have opportunities and not necessarily need to extract resources in an endangered forest or convert mangroves to other uses. Whatever the landscape is, it’s a challenge. It’s something that we’re still working with, but if there’s a general consensus that local people aren’t deriving benefits from biodiversity, it’s difficult to convince them without some other type of incentive that they should be collaborating.

Valentina: And I now have a question. If we think about that power, you mentioned people, institutions. We can think of power at the family level in men, women, youth. Can you make some examples of what would be the entry points to move all these levers in a nested way in the landscape, starting maybe from family and participation. How do you activate?

Kim: So in a sense, how do we locate? And I think that you touch on a really good point here, that the power is relative. You can’t have somebody all by themselves and then they’re powerful. It’s power over, power with, or power under. And so we get that immediately when two people or groups come together, the power surges – possibly in positive directions. Remember, power doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing.

Valentina: That’s why you want to empower.

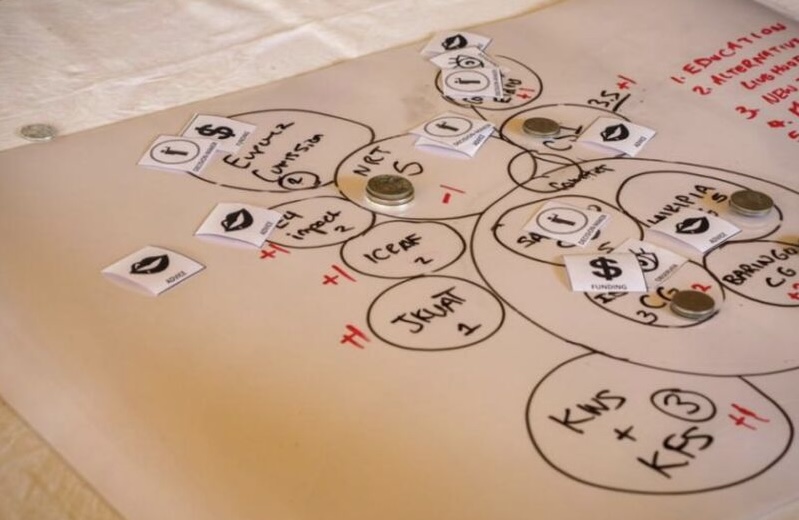

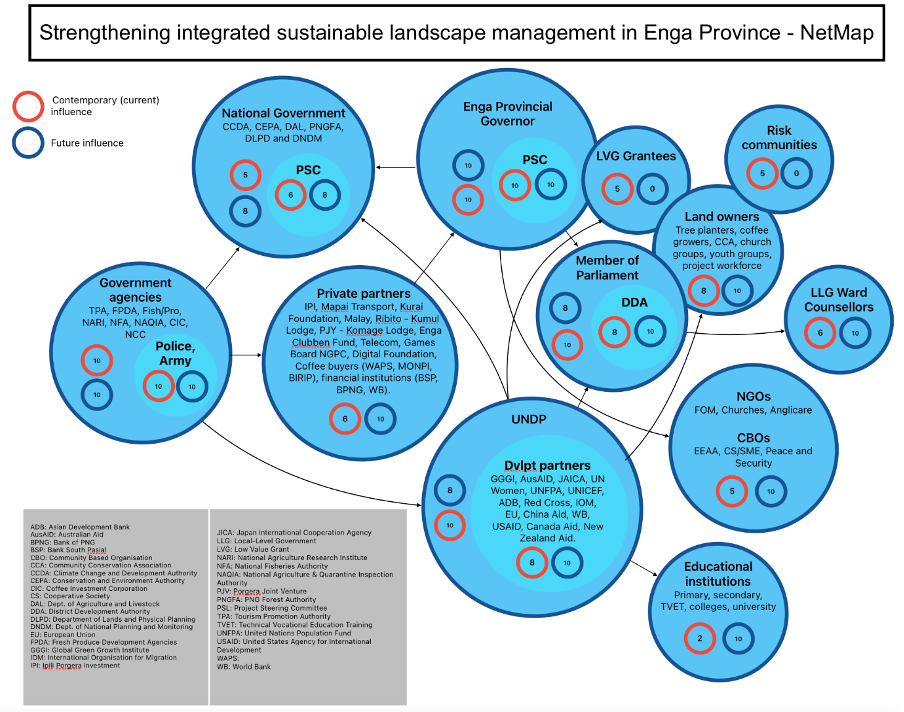

Kim: Exactly, because characterizing the landscape in power terms then becomes extremely relevant, alright. And what I often find very exciting is that other methodologies, or indeed emerging ones, look at how we are able to characterize power within the landscape. I don’t want to get technical, but one of the methods that we’ve been playing around with is this technique called Net-mapping. It’s a stakeholder approach, so we identify who the stakeholders are, but really the key thing is to be able to characterize the relationships between the stakeholders. I often say that it’s the in-betweenness of things that is relevant. It’s not the individual stakeholders by themselves. Of course, we like them, they’re good people, but it’s the relationships that they share with others that is of consequence to the landscape.

Valentina: So, you focus on the arrows?

Kim: Yes.

Valentina: Okay.

Kim: And characterize that as power under, power over or power under. And then we can begin thinking about strategies with which to change those relationships. I also think that what becomes really key here is that when we characterize those relationships it allows us to see where our risks lie within the landscape. I mean, if you’ve got a single completely unaccountable actor in the landscape, then we have to think about how we are going to address this presence within our system. And that then becomes very important to the overall success of a project.

And I just wanted to touch on a final thing here: what has always been very surprising to me is that, when we do these Net-maps with individual projects, the projects very rarely locate themselves in the map, and this I find very interesting. I think maybe it’s because they feel modest and they don’t want to suggest that they have an unnatural presence within the landscape. But, equally, in the absence of them being located in the landscape, we don’t get a sense of what that project needs to be doing in terms of changing those different relationships between partners. Then, equally, what does the project need to do for itself in order to be successful? Which relationships does it need? Which relationships does it have to manage? Which relationships does it want to avoid? This is also a key thing.

And then we can begin thinking about strategies with which to change those relationships. I also think that what becomes really key here is that when we characterize those relationships it allows us to see where our risks lie within the landscape. I mean, if you’ve got a single completely unaccountable actor in the landscape, then we have to think about how we are going to address this presence within our system. And that then becomes very important to the overall success of a project

Kim Geheb

Valentina: I think that happens because practitioners come into a landscape and exercises like stakeholder mapping, Net-mapping, are considered like “let’s state a baseline.” So when you do a baseline, you want to be neutral. It has to be the picture of your landscape, so you don’t put yourself in the picture.

Kim: Because you’re painting, right?

Valentina: Right, absolutely. So I think that’s something that’s an important message. One thing that for me is very important is how do we understand because there are actors… We recently made an assessment of the gender work we did in Peru, where there are women who basically do not actively participate and don’t have much agency. So you, as an external actor, realize this huge gender gap but they don’t seem to be really aware of it, to the point that they’d say “no, but I don’t want to. I’m satisfied with my level of agency.” How do you intervene in a way that people might realize that they actually need to be empowered so that there has to be something?

Peter: We’ve been doing work on gender transformative approaches to conservation, to land tenure reform, different types of projects. And one of the mechanisms that we’ve found is very successful are simply exchanges where women can share their experiences, hear from others’ opportunities, particularly where women can interact with other women that have become leaders of organizations or enterprises. And they’ve reported to us that after going through these exchanges where they identify common ground, where they identify similar conflicts or challenges that they face and, hearing the experiences of how others have overcome those challenges, the women come out of those exchanges reporting greater confidence. More importantly, realizing that they already play those roles often in their communities, often behind closed doors. You know that women in some societies and some communities may not stand up publicly in a meeting and express their opinion, but they make sure their husband’s opinion expressed in public reflects their interests as well. But, when they start learning how other women have used strategies or come up with ways to start enterprises or organizations, those women start reflecting or talking to their neighbours, meeting with their daughters and talking about how they could take advantage of opportunities that they face, or that they could stake out positions for themselves within their community, within their association, that’s different. And one of the key aspects of gender transformative approaches is that you can’t change a power dynamic in a household or in a society without the involvement of men and women, so creating a situation where women might be empowered entails convincing men and boys that having women play a more active role in an enterprise or taking charge of an organization is in everyone’s benefit.

Valentina: So that, I think, is important because he’s also convincing the others that the actor should have more power. That reminds me of when we played that game during the Global Summit on the oil palm. And I think that that was a useful approach to make groups understand the different forms of power and the interplay of it. What are things gained or what are the other approaches that can be used to make people realize? We have Net-mapping; we have games to realize what the power dynamics are, how they interplay over time, and how do you make people realize that they can be changed? What can ILM practitioners do?

Kim: When Peter was talking just now, one of the things that occurred to me, of course, is that there are many different species of power. And how that then articulates itself is often something that we don’t necessarily realize when we walk into a situation. With our training and our experience, we’re kind of coached to look for particular types of power without necessarily observing other types.

Valentina: The dynamic is in the interplay.

Kim: Exactly. So, of course, we can’t make anybody do anything. That’s not our role ever, but it’s interesting to me that when we talk about the creation of opportunity, it’s possible to couch that in power terms: like creating new spaces where people feel that they can exercise their power. They can then move into that opportunity if they choose to do so. Multi-stakeholder fora can be these spaces, and I think we can then use these as a way of supporting people to explore what power they do have and what opportunities the projects are then bringing that may empower them in ways that then yield landscape level outcomes.

We’re now sitting in a great example of an immense power dynamic here in Northern Kenya. This is the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy. As a conservancy we can understand the power of this place in terms of, for example, land tenure. Land tenure is something that people in CIFOR-ICRAF pay a lot of attention to: the power of limiting the ability of people to access these resources here. And as we go out into this landscape, we focus very much on the wild animals within it, but the power is in the grass. It is the fodder that is out there. It is grass that lies at the centre of tensions between the large, Northern Kenyan, wildlife conservancies and the nomads and livestock keepers outside the conservancies. When tensions between them flare, it is about grass. So then, in our awareness of that relation, how can we ameliorate it? Our hosts here, the Northern Rangelands Trust, they recognize this and a big part of their interventions together with communities in this landscape is specifically looking at pasture. How can we improve pasture? How can we make sure that pasture is available during the dry season? This is an area very affected by climate change, so it’s difficult to predict what the climate or weather is going to be over the course of the year. How, under those circumstances, can we make sure that there is adequate fodder for the millions of cattle and goats that are out there, and which then support everybody’s livelihoods? These kinds of questions have everything to do with power.How, under those circumstances, can we make sure that there is adequate fodder for the millions of cattle and goats that are out there, and which then support everybody’s livelihoods? That then becomes an opportunity, so we need to begin thinking about these sorts of managerial interventions as power opportunities.

Valentina: I think you just mentioned an important thing. It’s not strictly related to power, but you are kind of saying that, in a landscape where, for example, you have all these objectives of conservation and the issue is conflicts and friction about grass, the solution can be outside. So you might say that your landscape is this, and the easiest thing is to define a system in relation to what we see here, but actually the solution is intervening on land that is outside the geographical boundaries of this area. And that’s really system thinking. I intervene in other areas, generate resources outside so that people reduce pressure on this. And I think that’s very important to understand, not only in terms of power dynamics or its systems.

Kim: But it’s also accountable. I mean an organization like NRT has a very large number of constituents spread all the way across Northern Kenya, which includes other wildlife conservancies as well as nomadic communities. So, here there’s a dynamic conversation around how to deal with this political grass: some want to allow neighbouring communities onto the conservancy provided they follow guidelines. They don’t want, of course, the land to be completely denuded of its vegetation cover. Other would rather only allow community cattle onto their land only when circumstances are severe – like during drought. Others still would rather not allow nomads onto their land ever.

This text has been edited for clarity and differs slightly from the original recording.