When you land in Mauritius, the first impression is one of dazzling beauty: emerald mountains rising above a turquoise lagoon, sugarcane swaying in the breeze, and pockets of deep green forest. As you step out of the airport, the first sign that greets you proudly proclaims: “Welcome to Mauritius – a Green Island.” Looking out towards the horizon, all you see are rolling green landscapes stretching to the sea. But it is a trick of the eye: these are not native forests, but vast expanses of sugarcane plantations. The island’s rich natural heritage has been reshaped over centuries, and beneath the surface of this apparent greenness lies a deeper story.

A story of centuries of ecological transformation. Since human arrival, Mauritius has lost almost 90% of its native forests, much of it cleared for sugarcane and settlements. Invasive plants and animals now dominate many landscapes, and the once-thriving populations of endemic species have been reduced to fragile fragments. It is this history that gives urgency to today’s efforts to restore and steward the island’s unique, globally relevant biodiversity.

The Mauritius from Ridge to Reef (R2R) project has taken up this challenge with a holistic vision: linking mountains, rivers, forests, and reefs into one continuous fabric of restoration. From weeding invasive plants on steep slopes, to encouraging community apiculture, to protecting coastal wetlands and coral reefs, the project is premised on the idea that resilience is only possible when land and sea are managed together.

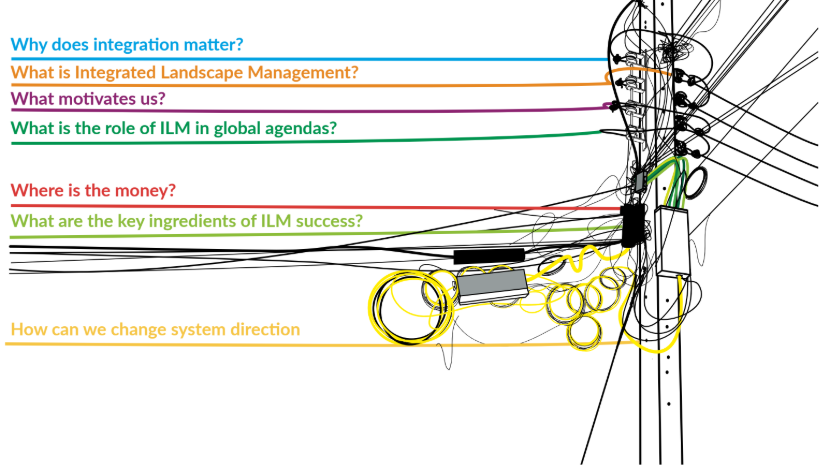

Restoration, however, is not only about plants and trees – it is about people. The conservation space in Mauritius has many actors: NGOs, government departments, and ministries whose mandates sometimes overlap. Collaboration among them must be strengthened. Restoration itself is a natural integrator: degraded land is found on coastal shores, within forests, and across agricultural landscapes. But for these efforts to truly benefit biodiversity, connectivity, and resilience, ecosystems – and the ministries responsible for them – need better integration.

Recognizing this, CIFOR-ICRAF this past month worked alongside partners to support a consultation workshop for the new Biodiversity Stewardship Platform (BSP).

Over three dozen participants gathered, representing a rich cross-section of Mauritian society: government ministries, NGOs, research institutions, youth representatives, private sector leaders, and local community organizations. Together, they grappled with a simple but profound question: how can Mauritius move from fragmented projects toward an integrated, long-term platform for stewardship?

The conversations were lively and candid. Stakeholders spoke of the need for a common vision, one that balances conservation with development, and puts equity at the heart of decision-making. Breakout groups wrestled with the design of the BSP — its governance structure, its functions, and how it could build credibility through transparency and inclusive participation. Ideas flowed: a communications hub to tell Mauritius’s biodiversity story; a knowledge-sharing system to capture lessons; and mechanisms for monitoring progress, so that commitments translate into results.

Workshop outcomes

By the close of the workshop, three major outcomes had emerged:

- A shared vision for the BSP as a national hub for coordination, learning, and action on biodiversity stewardship.

- Agreement on a draft structure, including a steering group and multi-stakeholder working groups to carry forward priority themes.

- Commitment to collaboration, with participants voicing readiness to contribute data, align projects, and champion the BSP across their networks.

There was a sense of possibility in the room — that Mauritius, despite its small size, can pioneer innovative governance for restoration and biodiversity.

We cannot afford to work in silos any longer. The Platform is where our efforts will finally meet.

BSP workshop participant

Looking ahead, the BSP will aim to knit together the many threads of biodiversity work across the island. Its ambition is to become a space where government, civil society, communities, and businesses co-create solutions, exchange lessons, and hold each other accountable. If successful, the Platform will not only accelerate restoration outcomes but also embed stewardship into the social fabric of Mauritius – ensuring that the island’s globally important natural heritage is cherished and safeguarded for the world.

Mauritius’s story, then, is one of both loss and renewal: centuries of degradation now giving rise to bold new approaches. The Ridge to Reef project shows what’s possible in practice; the BSP offers a governance model to sustain it. Together, they chart a hopeful course for an island that has long been defined by its nature, and whose future depends on it.