Our experience suggests that Integrated Landscape Management is a process for managing the competing demands on land through the implementation of adaptive and integrated management systems.

When combined with well-planned and executed technical interventions, ILM enables landscape multi-functionality to be managed, and its benefits to society and the environment to be captured and distributed.

Landscapes For Our Future Central Component

We see six critical elements in the Integrated Landscape Management (ILM) process. To see them in action, you need look no further than our programme’s remarkable Latin American and Caribbean projects, which have embraced the ILM approach to revolutionize land use practices, conserve biodiversity and foster sustainable development.

It is important that we understand what it is that we are integrating and managing when it comes to ILM. From our perspective, it is the people who make claims on the landscape that matter. Hence why the first two of our ILM ingredients focus on stakeholders. We see these organized behind a common vision, which they seek to reach through adaptive management and the right mix of tools. Finally, because the process works well, it is institutionalized

Kim Geheb, Coordinator, Central Component of the LFF

🇧🇴 Bolivia: Paisajes Resilientes

About the project

The department of Santa Cruz is part of the Amazon basin and comprises a large part of Bolivia’s lowland forests. It is home to numerous Indigenous communities and smallholder farmers who are highly vulnerable to poverty and climate-related risks. The department contains 78% of Bolivia’s biodiversity and supports 70% of the country’s agricultural production.

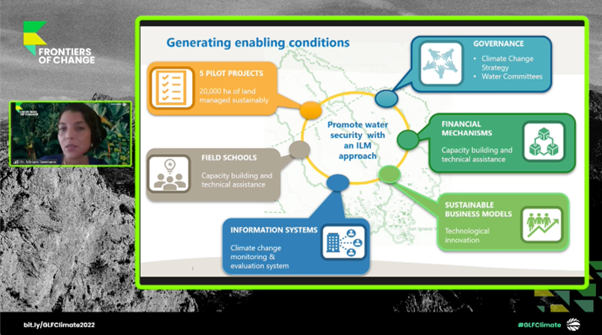

The Paisajes Resilientes en la Chiquitanía (Resilient Landscapes in the Chiquitanía) project, managed and implemented by GIZ, has made promising strides towards ILM to address the impacts of climate change in the the world’s largest preserved tropical dry forest and on the livelihoods of populations in nearby watersheds. It focuses on promoting water and productive security while strengthening governance structures and sustainable socio-economic activities.

Key ILM elements

Stakeholder identification

A key strength of the Paisajes Resilientes project lies in its robust stakeholder mapping exercises. The project utilizes the comprehensive Capacity Works tool to identify and engage relevant stakeholders in the landscape. This tool enables the project to assess the capacities and roles of different stakeholders, ensuring their active involvement and meaningful participation in decision-making processes. By mapping stakeholders and understanding their capacities, the project fosters stronger collaboration, builds local ownership, and enhances the overall effectiveness and sustainability of its interventions.

Multi-stakeholder Fora (MSF)

There is no MSF covering the entire landscape or functioning at the scale of the two watersheds making up the project area. However, there are several platforms that provide incipient foundations for MSFs within subunits in the project area. In each sub-watershed, the Paisajes Resilientes team has formed or reactivated Management Committees (Comités de Gestión), which are platforms composed primarily of representatives from communities participating in their pilot activities but also draw in other government actors, like municipal agencies, the municipal council, and the sub-gobernación (provincial government). Each management committee functions autonomously without coordination with the others.

In the Alto Paraguá sub-watershed, the Paisajes Resilientes team supported the creation of the MSF, strengthening the Asamblea Distrito (8th District Assembly), who leads it. In Bajo Paraguá and Tarvo, Paisajes Resilientes supported the strengthening of existing MSFs; and in the Alta sub-watershed, Paisajes Resilientes was behind the MSF’s reactivation. Community representatives are also involved the Asamblea Districto 8, which brings together cabildo representatives from communities in the sub-watershed of Alto-Paraguá.

The management committees have statutes and regulations designed specifically for each sub-watershed. In most cases, the Management Committees meet monthly, and once in a while the RLC team participates, to present advances related to their project.

These MSFs may pave the way for inclusive decision-making and potential collaboration, amplifying the project’s impact.

Common Vision

The Paisajes Resilientes team has organized a series of workshops to build collaboration among stakeholders around a common agenda. In signing a collaborative agreement with the Santa Cruz Departmental government, the project facilitated an inter-sectorial meeting with representatives of different agencies in the departmental government to dialogue needs and urgent issues to tackle. This was followed by a workshop with private sector and finance sector stakeholders.

Iterative and Adaptive Management

The Paisajes Resilientes project exhibits a strong commitment to reflection, learning and adaptation throughout its implementation. Recognizing the complexity and uncertainties associated with managing natural resources and ecosystems, the project continually assesses the effectiveness of its strategies, adapts to changing circumstances and integrates new knowledge and community perspectives into decision-making processes. This commitment is evident in the selection and design of pilot projects, which have been adjusted based on realities encountered in the field. For example, the exchanges of indigenous female leaders, initially planned as a single event, were expanded to multiple meetings due to their positive response. Similarly, the inclusion of apiculture and environmental education in the communication program, which were not initially defined in the project’s design, reflects the project’s adaptive planning and responsiveness.

Furthermore, the Paisajes Resilientes project places a strong emphasis on knowledge sharing and learning. It facilitates the exchange of experiences, best practices, and lessons learned among different stakeholders, including local communities, government agencies, and partner organizations. This collaborative learning approach enables the project to leverage collective knowledge, build on successful approaches, and adapt strategies based on shared experiences. By fostering a culture of learning and continuous improvement, the project strengthens its capacity to address complex challenges, promote innovation, and achieve long-term sustainability in the landscapes it works in.

Institutionalization

The project also excels in cultivating partnerships with the local and regional governmental actors responsible for governing the landscape. The Santa Cruz Departmental Assembly, a legislative body approving departmental policies, has closely aligned itself with the project’s objectives, providing a solid foundation for transformative change. Similarly, the Municipal Government of San Ignacio de Velasco, with its mandate to provide essential services and public works, has emerged as a robust ally, fostering positive local dynamics. These partnerships enhance the project’s potential for impact, engaging stakeholders who possess the power to effect change in the landscape.

Learn more from this project

A notable strength of the Paisajes Resilientes project is its adoption of a nested approach to landscape management. Recognizing the complexity and scale of the landscapes involved, the project divides the areas into sub-watershed units. This approach allows for a more focused and targeted implementation of interventions within specific ecological units. By addressing the unique characteristics and challenges of each sub-watershed, the project team tailors its strategies and actions to the specific needs and opportunities of different areas, thereby enhancing the effectiveness and impact of its interventions. Furthermore, the establishment of the sub-watersheds’ Management Committees, serving as a multi-stakeholder platform for diverse stakeholders to convene — even those who seldom interact in the landscape — paves the way for inclusive decision-making and potential collaboration, amplifying the project’s impact.

🇧🇷 🇵🇾 Brazil/Paraguay: CERES

About this project

One standout project in Latin America and the Caribbean is the Cerrado Resiliente (Resilient Cerrado) project, CERES. Led by WWF Brazil, WWF Paraguay, and the Institute for the Preservation and Promotion of Indigenous Peoples, CERES is a holistic project that focuses on the intricate interconnections between agriculture, natural resources, and rural livelihoods.

The Cerrado Biome is the world’s most biodiverse savanna, covering more than 2 million km2 in Brazil and Paraguay. It is home to 83 different Indigenous groups and communities, who have received varying degrees of recognition and land tenure. The Cerrado provides crucial ecosystem services at national, regional and global scales, supplying 70% of the country’s agricultural output and 44% of its exports.

Key ILM elements

Multi-stakeholder Fora (MSF)

By bringing together diverse stakeholders, including farmers, researchers, and policymakers, CERES creates a collaborative platform for knowledge exchange and action.

CERES also recognizes the significance of promoting sustainable value chains in responsible land use. Through its collaboration with the Tamo de Olho initiative, CERES further enhances its impact. Tamo de Olho (meaning “We’re Watching” in Portuguese) is a community-driven monitoring program that engages local communities in the collection and analysis of data related to land use, deforestation, and conservation. By involving communities as active participants in monitoring efforts, CERES fosters a sense of ownership and strengthens local knowledge systems.

WWF Paraguay, responsible for implementing the CERES project in the Alto Paraguay landscape, has successfully engaged small, medium, and large ranches through a multistakeholder forum that highlights shared interests among stakeholders. WWF Paraguay’s efforts have resulted in significant collaboration among diverse stakeholder groups, focusing on the Bahía Negra district’s land use management plan, known as POUT (Plan De Ordenamiento Urbano y Territorial).

The POUT roundtable was established as an MSF to support the POUT process. It facilitated dialogues and feedback from a wide variety of government, private sector, producer associations, indigenous communities and NGOs in the landscape. Their participation was driven by the desire to have their interests represented in the final land use planning process. Valentina Bedoya, WWF Paraguay’s Sustainable Landscapes Officer, emphasizes that the POUT Roundtable, initially established with a specific goal, has evolved into an entry point for multi-stakeholder dialogue that was previously lacking in the landscape.

The POUT Roundtable has proven to be a successful mechanism for participatory decision-making and consensus-building regarding land use in the territory, a sensitive topic because it touches on people’s livelihoods. However, an important lesson learned, says Patricia Roche, WWF Paraguay’s Project Specialist, is the need to empower governmental authorities to lead these spaces effectively. As highlighted by Roche, “It is crucial for these platforms to be led and convened by local or national authorities, as certain interest groups may view international NGOs as outsiders with conservation biases that could influence the outcomes.”

Institutionalization

CERES has successfully established partnerships with government agencies, local organizations, and indigenous communities, fostering a collaborative approach to integrated landscape management. This institutionalization ensures that the project’s strategies and initiatives are embedded within existing frameworks, policies, and governance structures, leading to long-term sustainability and impact.

Learn more from this project

CERES stands out for its ability to support decision-making, providing stakeholders with valuable tools and knowledge for informed choices. Leveraging cutting-edge technologies like remote sensing and data analytics, CERES guides informed decision-making and optimizes resource use. For instance, the project employs satellite imagery to assess land cover changes and identify priority areas for conservation and restoration efforts. CERES also emphasizes precision agriculture, enabling farmers to adopt sustainable practices tailored to their specific landscapes and challenges.

Through its comprehensive research and monitoring efforts, CERES generates reliable data on land use, biodiversity, and ecosystem services, enabling evidence-based decision-making. This approach helps stakeholders understand the potential social, economic, and environmental impacts of different land management practices and guides the development of sustainable strategies. Moreover, CERES facilitates capacity building and knowledge exchange among stakeholders, empowering them to actively participate in decision-making processes and implement effective solutions for ILM.

CERES fosters transparency and accountability along value chains, encouraging responsible production and consumption. By promoting sustainable sourcing and traceability, CERES ensures that products reaching the market are produced in a manner that safeguards ecosystems, respects workers’ rights, and contributes to local communities’ well-being. The Central do Cerrado Cooperative, a key partner supported by the CERES project, represents a collective enterprise combining multiple stakeholders to develop and maintain a productive value chain with standout products that include wild, endemic Non Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) such as the prized barú nut which is gathered from the wild. This initiative has gained traction among consumers, who increasingly prioritize ethical and environmentally-friendly products. By promoting sustainable value chains, CERES contributes to the economic viability of integrated landscapes management, creating market incentives for sustainable practices and supporting the livelihoods of local communities.

Read more about the CERES project’s sustainable cattle ranching.

🇨🇴 Colombia: Paisajes Sostenibles

About this project

Palafittic community in the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta, Colombia

Paisajes Sostenibles (Sustainable Landscapes) is a project in Colombia coordinated by FAO. It aims to promote sustainable land and resource management practices, biodiversity conservation and improving local community livelihoods. By integrating social, economic and environmental dimensions, the project seeks to achieve a balance between conservation and development in two landscapes: the Colombian Caribbean and the Central Andes.

The project is part of the larger private-public initiative called Herencia Colombia (HeCo), led by the Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development and National Natural Parks. Other project partners include WWF Colombia, the Institute for Marine and Coastal Research José Benito Vives de Andréis (INVEMAR), and the Instituto Alexander von Humboldt.

Key ILM elements

Common vision

Focusing on the Caribbean landscape, INVEMAR plays a pivotal role in addressing trust-building and supporting alternative sustainable livelihoods in vulnerable communities. For instance, INVEMAR collaborates with the palafitic communities in the Ciénaga Grande de Santa Marta area. Heavily reliant on fishing, these communities have been significantly affected by climate change and the armed conflict. Through capacity-building programs, infrastructure development, and marketing support, INVEMAR empowers communities such as these to establish sustainable ecotourism enterprises. These initiatives not only provide alternative sources of income but also contribute to the conservation of ecosystems and cultural heritage. INVEMAR’s holistic approach, integrating trust-building efforts with sustainable livelihood opportunities, ensures the well-being and resilience of these communities.

Technical solutions and tools

One of the standout features of the Paisajes Sostenibles project is the financial sustainability platform for entrepreneurs, led by WWF Colombia. This dynamic platform empowers local entrepreneurs involved in sustainable activities within the project landscapes. By providing access to funding, technical assistance and business mentorship, WWF Colombia supports the growth of environmentally responsible businesses. Through this platform, entrepreneurs can pursue resilient livelihoods while contributing to the conservation of natural resources, creating a win-win scenario for both communities and the environment.

🇪🇨 Ecuador: Paisajes Andinos

About the project

The Paisajes Andinos project aims to use an integrated landscapes approach to promote sustainable livelihoods and protect Andean ecosystem services. Implemented by Food and Agriculture Organization, in collaboration with the Ministry of the Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition and the Ministry of Agriculture and Cattle, it operates in multiple parishes across four of Ecuador’s provinces in collaboration with local associations and communities to implement a range of activities that support organic agriculture, value chain development, capacity building, and market access for agricultural products.

Key ILM elements

Multi-stakeholder fora (MSF)

The Paisajes Andinos project actively participates in the early stages of the Minga de Montaña, a community of practice that brings together various landscape management projects and stakeholders, serving as an MSF for coordination, knowledge sharing and collaboration among different initiatives in the region. By engaging in this community of practice, the project avoids overlap, learns from others’ experiences and contributes to the development of effective landscape management approaches. This collaborative network strengthens the overall impact and outcomes of landscape management projects, promoting integrated and holistic approaches to sustainable development.

Technical solutions and tools

The Paisajes Andinos project demonstrates exceptional strengths in monitoring and evaluation, leveraging a range of advanced tools and technologies to collect, analyse and interpret data. One notable aspect is the project’s utilization of System for Earth Observation Data Access, Processing, and Analysis for Land Monitoring (SEPAL) tools for satellite data analysis. By harnessing the power of satellite imagery, the project can monitor land cover changes, vegetation health, and other environmental indicators. SEPAL tools enable the project to access near real-time data, facilitating the identification of areas that require intervention and providing valuable insights for adaptive management.

Additionally, the project employs KoboToolbox, an open-source data collection platform, to gather field-level information efficiently. Through this tool, project staff and community members can collect survey data, track progress, and monitor indicators in a systematic and streamlined manner. KoboToolbox’s user-friendly interface and customizable forms enhance data quality and enable real-time data analysis, empowering the project with up-to-date information for decision-making.

Furthermore, Paisajes Andinos makes effective use of OpenForis, a suite of open-source software tools for environmental data collection and analysis. OpenForis facilitates the design of complex surveys, enables systematic sampling and supports data validation and quality control.

The project also benefits from SAP Crystal Reports, a data visualization and analysis platform. Crystal enables the project team to transform complex monitoring and evaluation data into clear and insightful visual representations, such as interactive maps, graphs, and charts. These visualizations facilitate data interpretation, communication and knowledge sharing among project stakeholders and decision-makers, supporting evidence-based decision-making and promoting transparency.

By leveraging these tools, the project ensures accuracy and reliability in the collection of data related to biodiversity, forest cover and other environmental parameters, contributing to robust monitoring and evaluation processes. By harnessing their capabilities the Paisajes Andinos project demonstrates a strong commitment to utilizing cutting-edge technologies in its monitoring and evaluation efforts.

Learn more from this project

One of the key strengths of the Paisajes Andinos project lies in its work around productive, sustainable value chains, with a notable example being its focus on the production of organic panela, an unrefined cane sugar. The project provides essential infrastructural support to enable farmers to qualify as organic panela producers, including the enhancement of ovens for more efficient production processes. Moreover, the project encourages diversification of products by supporting the production of other crops alongside panela. This diversification not only adds value to the farmers’ offerings but also contributes to their overall resilience. The project promotes sustainable production practices, such as selective harvesting and environmentally friendly approaches, while providing capacity building and training programmes to improve farmers’ skills and knowledge. Furthermore, through organic certification and collaboration, the project facilitates international market access for organic panela, creating broader market opportunities for farmers and increasing their income potential.

🇭🇳 Honduras: Mi Biósfera

About this project

The Integrated Management Project for the Río Plátano Biosphere (Mi Biósfera) aims to protect the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve, which is one of the last remaining tropical rainforests in Central America and is rich in biodiversity. Mi Biósfera’s objective is to reduce deforestation, protect biodiversity, and improve food security in a pilot area of the biosphere reserve. It focuses on promoting sustainable and integrated landscape management systems through agricultural value chains and zero deforestation approaches.

The project is divided into five components, including strengthening landscape management, fostering livestock and coffee value chains, implementing a climate financing mechanism, restoring degraded forest areas, and generating knowledge related to climate, biodiversity, and livelihoods.

Coordinated by the Honduran National Institute for Forest, Protected Areas and Wildlife Conservation and Development, the project involves several institutions, including the Zamorano Panamerican Agriculture University, the Honduran Foundation for Rural Business Development, the National University of Agriculture, and the Presidential Climate Change Office, Climate Plus.

Key ILM elements

Stakeholder identification

Preliminary information to map key stakeholders for the Mi Biósfera project’s interventions, the team used a methodology called the ‘Key Stakeholder Mapping’. This is a rapid assessment method that allows the team to understand, in a simple way, the social realities in which the project is immersed, the potential stakeholders present in a territory, how they interact with each other, what their beliefs, values and behaviour are and how they are defined, as well as their perceptions and their influence on the implementation of the Mi Biósfera project.

Iterative and adaptive management

The Mi Biósfera project also benefits from its integration of scientific research and monitoring. By collaborating with universities, research institutions, and environmental experts, the project has access to cutting-edge knowledge and expertise in the field of conservation and sustainable development. This scientific approach allows for evidence-based decision-making and the continuous evaluation of project outcomes. Monitoring systems are in place to assess the effectiveness of conservation measures, identify emerging challenges, and adapt strategies accordingly. The integration of research and monitoring ensures that the project remains adaptive and responsive to the evolving needs of the ecosystem and the communities it serves. It also provides a valuable platform for knowledge exchange and the dissemination of best practices, both within Honduras and globally, contributing to the broader field of conservation and sustainable development.

Learn more from this project

One notable strength of the Mi Biósfera project lies in its work around productive zero-deforestation cattle ranching. By implementing innovative techniques and practices, the project has reduced carbon emissions associated with cattle farming. Through measures, such as the use of rotational grazing and improved pasture management, the project has minimized the environmental impact of cattle ranching while maintaining high productivity levels. The adoption of sustainable wiring and solar panels for energy supply in ranching operations has further reduced reliance on fossil fuels and contributed to lower carbon emissions. These climate-smart farming practices have demonstrated the efficienct use of land, allowing for increased cattle stocking rates without compromising environmental sustainability.

Model farm developments have been established to showcase these practices as examples of better resource management, attracting other farmers to adopt similar sustainable and climate-smart farming approaches. The project even reported successful outcome stories in which at least two model farms, Miguel Arias’ Las Marías and Ramón Santos’ Río Negro-Pisijire, have a negative carbon balance. Other positive outcomes include improved soil quality, enhanced water conservation, and increased revenues for farmers, all achieved with fewer human and financial costs.

Read more about sustainable cattle ranching in Latin America and the Carribbean.

🇯🇲 Jamaica: Hills to Ocean

About this project

A Jamaican Path from Hills to Ocean focuses on increasing resilience to climate change and reducing poverty through integrated and sustainable landscape management in three selected watershed management units (WMUs). Its goal is to support community-based organizations, including farmers, fisherfolk, entrepreneurs, and environmental groups, in improving their management and stewardship of targeted areas. A key aspect of the project’s objective is to address the negative impacts of hillside farming, such as soil erosion and landslides during the rainy season.

Executed by the Planning Institute of Jamaica, the project’s technical implementation is carried out by the Rural Agricultural Development Authority and the Public Gardens Division, both under the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, and the National Environment and Planning Agency.

Key ILM element

Institutionalization

One salient characteristic of this project lies in the involvement of main implementing agencies that possess mandates for policy action in the landscapes. Agencies such as the National Environment Planning Agency, the Forestry Department, and the Fisheries Division have the authority and expertise to enforce regulations and guidelines for sustainable resource management. Leveraging their legitimacy and institutional capacity, these agencies play a key role in convening stakeholders, including local communities, businesses, and civil society organizations. Through collaborative platforms and participatory processes, they facilitate dialogue, build consensus, and promote sustainable practices. The agencies’ involvement ensures the alignment of policies and actions across different sectors, fostering a holistic and integrated approach to landscape management.

Learn more from this project

During its initial phases, the H2O project conducted a Rapid Ecological Assessment (REA) through the University of the West Indies (Mona). This assessment specifically focused on understanding the dynamics and health of ecosystems in the selected WMUs. It referred to stakeholder activity driving degradation as well as stakeholder impacted by degradation trends. The REA reported data on the level of “resilience” of informants surveyed in each of the WMUs. This assessment served as a basis to identify priority areas for project intervention efforts.

Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States: OECS-ILM

Les Pitons, Soufriere town and surrounds, Saint Lucia

Forest with ecotourism potential in Soufriere watershed, Saint Lucia

LFF Latin America and Caribbean team with OECS-ILM Grenada team at Grand Bacolet Estate, Grenada.

Finca, Grand Bras, Grenada

About this project

This project, implemented by the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) and its member states, encompasses nine individual projects tailored to the unique situations of each island. Among these, three (in Anguilla, Dominica, and Grenada) are classified as ILM projects, while six (in Antigua and Barbuda, the British Virgin Islands, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines) are categorized as isSimple Land Management projects.

The primary objective is to address challenges such as land degradation, deforestation, and biodiversity loss, with a focus on promoting sustainable land management practices and enhancing ecosystem resilience. The overall project aims to optimize land’s contribution to agriculture, food security, climate change mitigation and adaptation, while preserving ecosystem services and improving the quality of life for stakeholders, including local farmers and communities in selected watersheds and geographic locations.

Key ILM element

Institutionalization

A noteworthy characteristic of the OECS-ILM project is its comprehensive approach that spans nine initiatives across small island developing states. Each initiative is designed to tackle specific issues related to land degradation and sustainable land management, employing customized strategies and interventions based on the individual island’s unique needs and challenges. This diversity of projects provides opportunities to enhance the effectiveness and relevance of the overall programme, as it recognizes the distinct characteristics and requirements of each participating island.

Learn more from this project

Recognizing the significant potential of agroforestry systems, the OECS-ILM project places particular emphasis on their application in countries like St Lucia and Grenada, where they can help mitigate risks associated with hillside farming and soil erosion, especially in hurricane-prone areas. These systems offer opportunities to harness the benefits of trees and perennial crops within agricultural landscapes.

In Grenada, the project focuses on promoting agroforestry systems that support the cultivation of valuable crops such as nutmeg, cocoa, and other species, which are well-suited to the local conditions and have economic significance. Similarly, in St. Lucia, the initiative aims to establish agroforestry options to diversify existing farming systems, which are currently dominated by dasheen monocultures. Additionally, St. Lucia plans to create an agro-tourism park, further diversifying income sources and promoting sustainable land use practices.