Today, the Sustainable Integrated Landscape Management in the Gonarezhou National Park and surrounding communities project is regarded as one of the strongest role models amongst the 22 projects in the Landscapes For Our Future programme, not because SAT-WILD and the other project partners had all the answers from the start, but because they have remained committed to facilitation, co-creation, and adaptive learning. Lemson’s reflections offer invaluable guidance for anyone working with communities on complex, long-term landscape challenges.

Begin with respect

For Lemson, the starting point is simple but powerful: treat communities as equals. “View them as people with the same potential and capability in achieving goals,” he says. Respect isn’t just an attitude – it’s also shown through action.

That means recognizing and following local structures. Traditional leaders such as chiefs and headmen hold important roles, and there are established cultural protocols for introducing yourself. “If you don’t follow their procedures, you’ll struggle to penetrate those communities.”

Respecting these systems signals humility and seriousness. It opens the door for collaboration rather than confrontation.

Work through local voices

Language can be a barrier – or a bridge. Lemson speaks Ndebele and Shona, but in Gonarezhou most people use Tsonga or Shangaan. Rather than seeing this as an obstacle, he teamed up with colleagues from the area who can translate and explain cultural nuances.

Communication, he stresses, isn’t just about words. It’s about ensuring that everyone understands, feels included, and sees themselves in the process. That often requires adapting your methods.

Make it practical and participatory

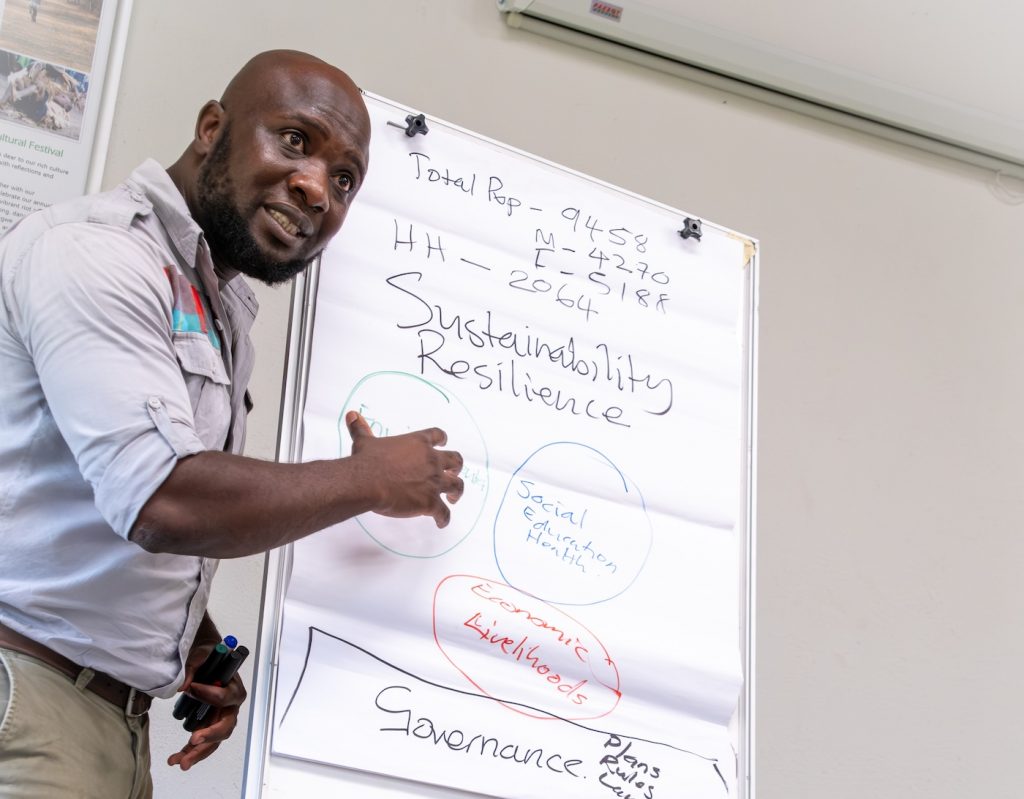

“We are not there to deliver PowerPoints,” Lemson says with a smile. In communities where abstract diagrams don’t resonate, SAT-WILD uses props and local metaphors.

- A sponge becomes a model of resilience – it can be squeezed but always bounces back, and it holds water for future use.

- A three-legged cooking pot illustrates sustainable development: social, environmental, and economic “legs” must all be balanced, while governance provides the base.

By drawing on everyday objects, facilitators turn complex concepts into something tangible, memorable, and actionable. Group work, illustrations, and hands-on activities ensure that knowledge is not just shared but co-created.

Value indigenous knowledge

Too often, practitioners treat communities as “empty jars” to be filled with external expertise. Lemson rejects this model. “They already have water in their jars,” he insists. Communities bring rich indigenous knowledge and lived experience that must be woven together with scientific and technical insights.

By asking “What do you know about this?” facilitators create space for dialogue. That blending of perspectives doesn’t just build better solutions – it builds ownership. And ownership is what makes projects last beyond donor cycles.

Stay flexible

Development timelines are often tight, but rigid schedules rarely work on the ground. Community events, ceremonies, or farming activities may clash with planned workshops. Lemson’s advice: don’t force it.

“Be flexible to change, tailor-make activities to fit into their plans, and work with them,” he says. “We are not at war. We are one big family wanting to achieve greater work in the landscape.”

Facilitate for co-creation

Ultimately, Lemson sees his role not as leading but as facilitating. SAT-WILD doesn’t claim the project as its own. “It’s not our project – it’s their project,” he explains, referring to the communities and other partners, including Malipati Developmentt Trust, Ngwenyeni Community Environment & Development Trust, local Authorities, Gonarezhou Conservation Trust, Manjinji Bosman’s Community Conservation and Tourism Partnership and SAT-WILD “We are just coming as facilitators, working with them.”

That mindset transforms relationships. It shifts from top-down instruction to shared problem-solving. It builds resilience not only in communities but also in the partnerships that support them.

Conclusion: A role model for ILM

For practitioners working in Integrated Landscape Management, Lemson’s advice is clear: respect local structures, adapt communication, make learning practical, value indigenous knowledge, and remain flexible.

It sounds simple – and in many ways it is. But doing these things consistently, with patience and humility, is what allows trust to grow. And trust, as SAT-WILD’s experience shows, is the foundation of lasting change.