I fell in love with a long green line.

In late 2022, members of the Landscapes For Our Future programme’s Central Component visited Zimbabwe to learn from an impressive project that aims to restore land health and conserve wildlife habitat using an Integrated Landscape Management approach along boundaries of the Gonarezhou National Park and Malilangwe Wildlife Reserve.

And that’s where we became enamoured with a string of green. We drove mile after mile through the dust following its line. And then got out and walked it to unravel the how and why of it.

A narrow string of green atop a vast sea of black. Black cotton soils, as they are locally known, are highly fertile soils formed by incredibly fine clayey material. These soils are highly susceptible to erosion due to their low bearing capacity and shrink-swell properties. In this area they have been subject to immense erosion events, caused by rain, forming gullies and erosion of high intensity, sometimes washing away gigantic volumes of this precious topsoil.

It’s a somewhat bristly string, mind you. And one that initially did have locals bristling. Zimbabwe’s politics over the past 25 years has been very much defined by land and its grabs, so there were understandably low levels of trust when a former farmer came in and started planting vetiver grass (Chrysopogon zizanioides) on communal lands. But, as Norman Mugeveza, the local vetiver supervisor, explains, they eventually came round when its erosion-prevention role as well as its plethora of other benefits became apparent.

Muguveza’s conviction was compelling, but at this point, the extent of the problem remained unclear to us– and the true value of this low-tech solution vague.

Then we visited one of its apocalyptic raisons d’être: a reservoir in Malilangwe Wildlife Reserve that was filled with the soil of the communal lands around it.

This was a double problem: a reservoir filled with topsoil doesn’t provide much water for wildlife, particularly the white rhino and Lichtenstein’s hartebeest that the conservancy strives to protect. And surrounding lands without their topsoil don’t produce much sustenance for man or beast.

Great big earthmoving equipment – which required great big budgets – was set the task of removing that soil from the reservoir, but this was a slow and unending process. Not sustainable by any stretch of the imagination.

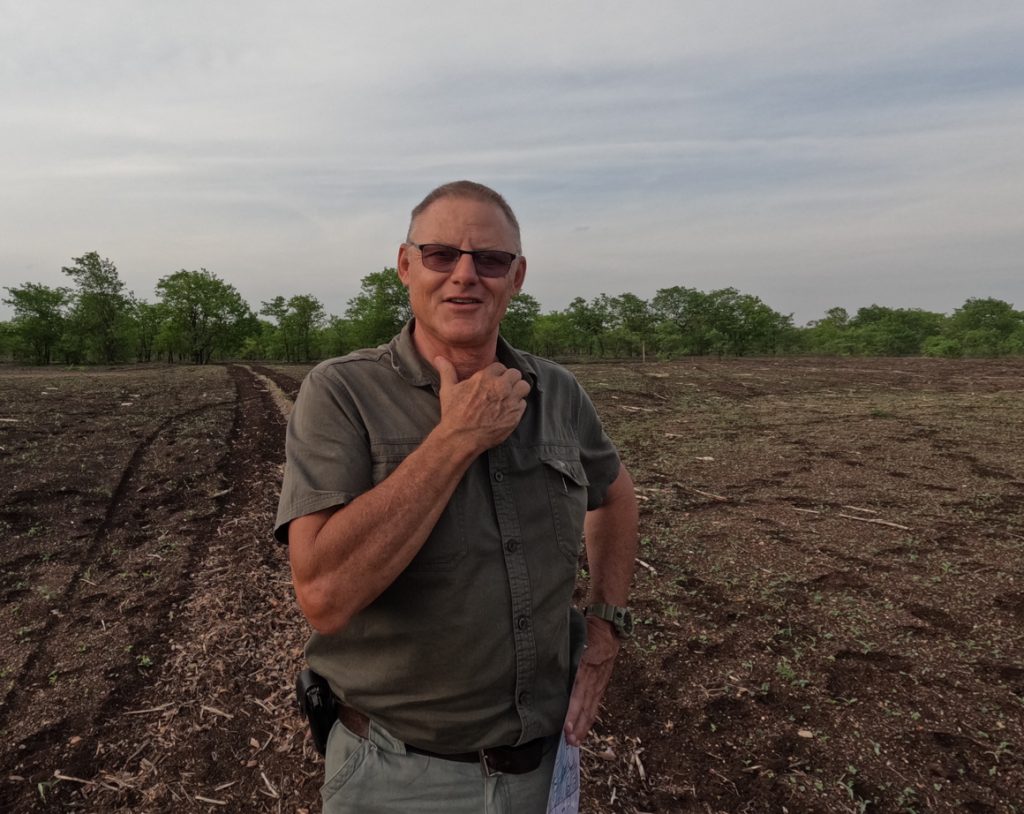

And there on that dam wall our team chatted to Graham Dabbs, one of the authors of ‘Zimbabwe – A partnership for soil erosion and flood control using the Vetiver System‘, a paper that describes the problem and this pilot solution in detail.

“The Chitsa Communal Land is situated in the semi-arid, south-eastern lowveld of Zimbabwe. People living in the area practice rain fed cultivation of sorghum and maize but because of the area’s low average annual rainfall (≈450 mm) and frequent droughts, adequate yields are only realised in four out of every ten years,” Dabbs and fellow author Bruce Clegg explain. “The inhabitants are poor, and live from hand-to-mouth, with little means to improve their lives. In recent decades, the demand for agricultural land in Chitsa has resulted in the clearing of large tracts of natural woodland. In many instances, clearing has been carried out with little regard for the protection of existing drainage lines, and this has led to uncontrolled runoff and the development of extensive networks of eroding rills and gullies.”

If left unchecked, soil erosion is predicted to render many of the fields useless within the next 15 years. This will be a tragedy of large proportions because thousands of people living in the area rely on cropping for their survival.

Dabbs is a former farmer and a man with a curious mind. He’d heard rumours of the miracles that could be performed with this low-tech tool.

“What if it really does work?” he’d thought as he dug deep into the existing research.

Finding keen collaborators in The Malilangwe Trust’s resident ecologist, Dr Bruce Clegg, and its executive director, Mark Saunders, and key commitment and finance from the Trust itself, he’s tested this theory that the skeptics had thought too good to be true. It’s a theory that is indeed showing great promise and two years into the project, appears to be yielding results.

As we stare at the depressing sight of these massive erosion deposits, he outlines how the earlier use of vetiver as a tool further upstream could have prevented this type of soil loss in the surrounding communal lands.

Compelling, right? Not only an anti-erosion device, but an anti-fungal mattress stuffer. What’s not to love about that? 🤔

Want to learn more?

Here again is the paper that Dabbs and Clegg wrote. It’s filled with detailed specifics: the how-tos, the costs, photos of the hedge establishment over time, and a key commentary on the cost-benefit analysis:

Is it possible to put a price on soil? Soil is replaced when rock weathers over geological time, which is measured in hundreds of thousands of years. This means that for human purposes soil cannot be replaced. If lost, it is gone forever. This, coupled with humanities’ absolute dependence on soil for survival, renders it a priceless natural asset.

We simply cannot afford to lose soil and should do everything in our power to conserve it. That being said, soil’s apparent abundance dampens the sense of urgency that should surround its conservation. All too often, full realisation of the problem happens too late – once the erosion juggernaut has already gained momentum and the problem has become very difficult or impossible to solve. It is our intention not to allow this to happen…

– Graham dabbs and bruce clegg