Designing for engagement: Insights for more equitable and resilient multi-stakeholder forums

If you’re not in the know on all things carbon market related, you’re not alone. But you are in the right place. We’ll try to answer your questions below.

In a nutshell, carbon markets are trading systems in which carbon credits are sold and bought. One tradable carbon credit is equal to one tonne of carbon dioxide or the equivalent amount of a different greenhouse gas which has been reduced, sequestered or avoided. This market mechanism, one of several policy tools touted to help address societal challenge of climate change and biodiversity loss, provides everyone from consumers to large corporations an avenue by which to reduce their own carbon footprint.

That’s the UNDP definition. And here they answer why carbon markets are important.

A carbon offset represents a reduction or removal of one metric tonne of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere that is used to compensate for emissions that occur elsewhere.

Carbon offsets can be generated by the reduction or removal of any greenhouse gas (GHG) known to cause climate change, but carbon dioxide is used as the point of reference because it is the most common GHG in the atmosphere and remains in the climate system for a very long time.

Carbon offsets have the potential to play an important role in minimizing the carbon footprint of large emitting organizations and individuals and can be used to counterbalance emissions that cannot be directly reduced, removed, or avoided.

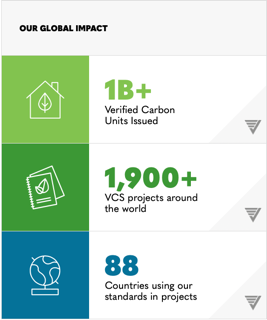

The carbon credits generated under Verra’s Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) programme are called Verified Carbon Units (VCUs). Source.

Yes. Broadly they fit two categories: compliance and voluntary.

Compliance markets are created as a result of any national, regional and/or international policy or regulatory requirement, and operate on a mandatory basis, created to meet carbon reduction targets, and are regulated by governments.

Voluntary carbon markets – national and international – refer to the issuance, buying and selling of carbon credits, on a voluntary basis, providing the grounds for additional actors to offset carbon emissions to meet their own sustainability goals or to demonstrate their commitment to reducing their carbon footprint. These markets are not regulated by government, and use third party verifiers to adhere to global standards.

And what role might it play in the global drive to reduce emissions? S&P Global’s video explains in a nutshell how carbon credits are created and traded in the VCM and who’s involved in the market. Source.

There is no single governing body which certifies carbon offsets, rather a collection of third-party companies develops global standards, validates and certifies carbon offsets projects. Each company has its own methodologies to legitimatize carbon removals from the atmosphere. Verra has been working since its inception in 2005 with leading scientists, conservationists, financiers and practitioners to establish a robust voluntary framework that enables society to value environmental benefits derived from project activities, including the protection of forests under threat through REDD – Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation,” explains Verra CEO David Antonioli. Source.

Through Verra, projects implementing activities that protect forests under threat can be certified and issued carbon credits that equate to tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) avoided.

In short, Verra’s REDD standards enable society to measure the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that are avoided by ensuring that forests at risk of being cut down or burned are kept standing. By valuing standing forests, REDD gives trees a fighting chance in the face of the numerous economic drivers that would otherwise do away with them.

Carbon markets represent an enticing and genuine opportunity for an alternative funding stream, to support landscape-based activities which aim to reduce emissions and increase resilience. Enticing as they may be, the space has recently been rife with tension as claims of phantom credits, inflated baseline figures and overestimation of carbon drawdown circle.

– Khalil Walji, Central Component Deputy Coordinator, Landscape For Our Future

“Carbon credits are increasingly used to neutralise the emissions of large companies, predominantly in the West,” notes Adriaan Korthuis, co-founder and managing partner of the climate consultancy and thinktank Climate Focus in episode 074 of the Bionic Planet podcast.

And typically, when corporates are accused of using offsets for… Well, not reducing in their own processes, then the automatic reaction is ‘then, okay, we should squeeze the projects and make sure that the quality of the carbon credits is good enough. Which does not make sense. Because if the problem is with the offsetting, then the solution should be with the offsetting, and not with the projects.

So in this turmoil of Voluntary Carbon Markets, the supply side – the side where the projects are taking place, was squeezed in discussion on offsetting and potentially greenwashing, and for that very reason the supply side needs to get a place on the stage itself and needs to make clear what is happening, and develop a narrative by itself so that people in voluntary carbon markets and around realise this is happening on supplier side ,and these are the problems that projects are facing, and this is the demand side and these are the issues we are debating about offsetting and greenwashing.

– Adriaan Korthuis

If you’re looking for an entry point to understanding the Anthropocene, there can be few better places to start than Bionic Planet. Producer and narrator Steve Zwick has a real talent for bringing clarity within complexity, as he does here to explain the Korthuis’s references to offsetting and greenwashing.

“By that he means we all worry that some companies might use carbon credits to avoid reducing emissions internally, but too many of us, instead of trying to address that issue, are trying to convince people that carbon credits don’t work.

In other words, if you want to make sure that companies are using carbon credits the way they are supposed to – namely to accelerate reductions rather than avoiding them – then you need to focus on how carbon crediting fits into corporate strategies.

That’s what the Voluntary Carbon Markets Credits Integrity Initiative, or VCMI, does.

Initiatives like the VCMI and the task force on scaling voluntary carbon markets get short shrift in most media, which is why so many outlets get the fundamental nature of carbon markets wrong.”

If you’re not paying close attention to the fundamental debates that underly these mechanisms, you won’t understand how they work or how they’re being utilised. Carbon markets have been evolving for more than 30 years and you can’t just parachute into them without doing some homework and expect to get them right.

– Steve Zwick, Bionic Planet

‘Revealed: more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows’ announced a headline in the UK’s The Guardian newspaper on 18 January this year.

The forest carbon offsets approved by the world’s leading certifier and used by Disney, Shell, Gucci and other big corporations are largely worthless and could make global heating worse, according to a new investigation.

The research into Verra, the world’s leading carbon standard for the rapidly growing $2bn (£1.6bn) voluntary offsets market, has found that, based on analysis of a significant percentage of the projects, more than 90% of their rainforest offset credits – among the most commonly used by companies – are likely to be “phantom credits” and do not represent genuine carbon reductions.

The analysis raises questions over the credits bought by a number of internationally renowned companies – some of them have labelled their products “carbon neutral”, or have told their consumers they can fly, buy new clothes or eat certain foods without making the climate crisis worse.

But doubts have been raised repeatedly over whether they are really effective,” began the article, written by Patrick Greenfield, the biodiversity and environment reporter for The Guardian and the Observer.

Almost immediately, The Guardian’s environment editor, Fiona Harvey, published an “analysis” piece that began in far more a conciliatory fashion: “Carbon credits and offsets do not have a great record but the funds they raise are a vital part in fight against deforestation.”

Verra responded with a rebuttal immediately and then later in the month with a technical analysis of the critique. CEO David Antonioli went on to explain:

Certifying REDD activities is not easy, in part because one has to quantify the risk of forest loss that would occur without the carbon project (i.e., the baseline). In other words, this requires counterfactual analysis, which is a fancy term for looking at a situation and asking what would happen if things were different. This approach isn’t unique to REDD and is a cornerstone of the impact analyses that government agencies, academics and others around the world use to determine what works, what doesn’t, and how to allocate resources.

Counterfactual analysis is, by its nature, impossible to confirm with 100 percent certainty, but is critical if we are to channel more resources to protecting forests as a critical means of fighting climate change.

Awarding carbon credits to REDD projects requires extreme diligence, and we take that challenge seriously. For example, we ensure wide consultation on the most up-to-date science and best practices, as well as a thorough understanding of the available tools to measure forest loss and gain. This has been Verra’s guiding approach since we embarked on this journey, and continues to this day.

Unfortunately… The Guardian and Die Zeit, working in tandem with the privately-funded ‘investigative non-profit’ SourceMaterial, published sensationalist articles using outlandish claims about the value of the REDD credits we have issued based on simplistic extrapolations of research that uses old, outlier statistical models. These are academically interesting exercises, but they would never pass muster as bona fide carbon crediting methodologies.

The saga continued last month when The Guardian triumphantly announced that “Verra will phase out the programme by mid-2025 after a Guardian investigation found it was flawed.”

A key fact to understand here is that the above is factually true, but the suggestion of causality is incorrect. Yes, the update took place after the investigation. But, as various commentators (such as this one on LinkedIn) pointed out, Verra had been preparing to update and consolidate its avoided deforestation methodologies since October 2020.

“Where does the science end and the politics begin?” asked Ed Hewitt, Natural Climate Solutions lead at Respira International, in his excellent round-up of resources and rebuttals to The Guardian’s article here on LinkedIn.

No. But don’t jump in blindly either. “Forest carbon offsets are a tool, not a silver bullet,” noted our CIFOR-ICRAF colleagues Robert Nasi and Pham Thu Thuy in a Mongabay commentary that is a must-read summary of the potentials and pitfalls:

Our purpose is not to take sides in this case, but rather to advocate for not ‘throwing out the baby with the bathwater.’ Nature and people-based solutions are more important than ever now, as we face the challenge of cutting emissions almost in half by 2030, with the goal of reaching net zero by 2050. This goal is not yet out of reach, but it requires urgent – and well-informed – action.

A high-quality carbon offset project has several key traits. It must have an exclusive claim to its greenhouse gas reductions, meaning the reductions would not have happened without the project (called “additionality” because the reduction would not have occurred in the absence of offset credits). It must accurately calculate its greenhouse gas emissions and reductions. The project should be certified by a reputable offset standard. And the offset should cause no harm to local communities or environments, ensuring that social safeguards and biodiversity values are well respected.

For more detailed information, download the VCS Programme Guide here.

Want some real-world inspiration on how REDD+ can facilitate results-based payments when equitably channelled through inclusive and effective community-based structures can look like? Read this story from Kenya, shared on LinkedIn by Joshua Tosteson, who notes that “the story brings the abstract concepts of “baseline accuracy” down to the ground and reminds us of the real purpose of REDD+, which is to halt deforestation by making conservation a viable economic choice – in the face of the opportunity cost of the alternatives. Those alternatives will perennially remain options, which is why we need the sustained financing from REDD+ to build a viable alternative economy for the long term.”

Additionality means that the reduction or removal of a greenhouse gas (GHG) emission arises from an activity that would not have occurred without the revenue from the sale of carbon credits. A first and critical step in this context is to determine that a project activity is not required by law or regulation.

All VCS-approved methodologies must include a detailed approach for determining the additionality of a specific project activity. The independent validation/verification body (VVB) audits the demonstration of additionality to conclude whether the project meets VCS rules and requirements. Source.

REDD and ARR are often combined and referred to as REDD+, which stands for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and fostering conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks.

In Dec 2021, Verra announced it was updating baseline, leakage, monitoring, and uncertainty procedures for Avoiding Unplanned Deforestation and Degradation (AUDD) project activities in order to facilitate their alignment with REDD+ jurisdictional programmes and Verra’s Jurisdictional and Nested REDD+ (JNR) rules.

The baseline is the reference point against which a project’s emissions reductions or removals are measured. The baseline scenario represents the activities and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that would occur in the absence of a project. It is determined according to the specific carbon accounting methodology applied to the project.

Emission reductions or carbon removals in excess of the baseline level are considered additional and, thus, eligible to generate a carbon credit. Source.

When a carbon credit is used to compensate for emissions elsewhere, it is “retired”, i.e., taken out of circulation and can no longer be sold; at this point, a carbon credit becomes a carbon offset.

Defined in Article 12 of the Kyoto Protocol, this allows a country with an emission-reduction or emission-limitation commitment to implement an emission-reduction project in developing countries. Such projects can earn saleable certified emission reduction (CER) credits, each equivalent to one tonne of CO2, which can be counted towards meeting Kyoto targets.

The mechanism is seen by many as a trailblazer. It is the first global, environmental investment and credit scheme of its kind, providing a standardized emissions offset instrument, CERs.

A CDM project activity might involve, for example, a rural electrification project using solar panels or the installation of more energy-efficient boilers. The mechanism stimulates sustainable development and emission reductions, while giving industrialized countries some flexibility in how they meet their emission reduction or limitation targets. Source.

When compliance credits go from one country to another, they involve an actual transfer of an emission reduction from the host country’s national carbon inventory to the buying country’s national carbon inventory. Voluntary carbon markets are different, because the unit of reduction doesn’t go from one country to another, instead the climate impact is factored into the emissions of the country where it took place – the host country. A company that buys the credit, in a buying country, gets credit for helping the first country reduce its emissions, but that credit doesn’t impact the buying country’s national account. Source.

Once an ERR has been certified under a reputable standard, it can be issued as a tradable unit and is called a “carbon credit”.

One type of compliance market that many people will have heard of, ETS operate on a “cap-and-trade” principle in which regulated businesses – or countries, as in the case of the European Union’s ETS – are issued emission/pollution permits, or allowances by governments (which add up to a total maximum, or capped, amount). Polluters that exceed their permitted emissions must buy permits from others with permits available for sale (i.e., trade). Source.

The European Union launched the world’s first international ETS in 2005. Last year, China launched the world’s largest ETS, estimated to cover around one-seventh of global carbon emissions from the burning of fossil-fuels. Many more national and subnational ETS are now operating or under development.

The VCS Jurisdictional and Nested REDD+ (JNR) Framework is the world’s first accounting and verification framework for jurisdictional REDD+ programs and nested projects. Source.

Adopted in 1997 and entering into force in 2005, the Kyoto Protocol operationalizes the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change by committing industrialized countries and economies in transition to limit and reduce greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions in accordance with agreed individual targets. The Convention itself only asks those countries to adopt policies and measures on mitigation and to report periodically.

One important element of the Kyoto Protocol was the establishment of flexible market mechanisms, which are based on the trade of emissions permits. Under the Protocol, countries must meet their targets primarily through national measures. However, the Protocol also offers them an additional means to meet their targets by way of three market-based mechanisms:

These mechanisms ideally encourage GHG abatement to start where it is most cost-effective, for example, in the developing world. It does not matter where emissions are reduced, as long as they are removed from the atmosphere. This has the parallel benefits of stimulating green investment in developing countries and including the private sector in this endeavour to cut and hold steady GHG emissions at a safe level. It also makes leap-frogging—that is, the possibility of skipping the use of older, dirtier technology for newer, cleaner infrastructure and systems, with obvious longer-term benefits—more economical. Source.

In their NDCs, countries communicate actions they will take to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in order to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement. Countries also communicate in their NDCs actions they will take to build resilience to adapt to the impacts of climate change. Source.

The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty on climate change. It was adopted by 196 Parties at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in Paris, France, on 12 December 2015. It entered into force on 4 November 2016.

Its overarching goal is to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”

Since 2020, countries have been submitting their national climate action plans, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Each successive NDC is meant to reflect an increasingly higher degree of ambition compared to the previous version. Source.

REDD is the abbreviation for “reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation”, followed by REDD+, with the “plus” referring to “the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhance- ment of forest carbon stocks in developing countries”.

In a nutshell, REDD+ can be perceived as a payment for ecosystems services scheme. It offers developing nations and their people a financial incentive to keep their forests intact. Source.

The UNFCCC secretariat (UN Climate Change) is the United Nations entity tasked with supporting the global response to the threat of climate change. The Convention has near universal membership (199 Parties) and is the parent treaty of the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The VCS Programme has certified the largest number of REDD+ projects around the world.

The VCS Jurisdictional and Nested REDD+ (JNR) Framework helps entities with forest-related emission reduction activities to integrate their efforts into governmental climate goals. It also gives governments a framework to generate greenhouse gas credits for their REDD+ programmes and to nest projects and other site-specific, lower-level efforts (a tourism operation, a new agroforestry planting, a new governance initiative to control illegal deforestation). Linking site-level forest conservation with jurisdictional goals, capacities, and resources allows governments to incentivize conservation and accelerate progress toward their long-term climate objectives.

In 2021, the Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM) Global Dialogue undertook a comprehensive and extensive stakeholder consultation process about moving the supply-side of the voluntary carbon market into the centre of discussion about how these markets can be best designed and deployed.

The VCM Global Dialogue’s final report sets out six principles to maximize the contribution of the VCM to ambitious climate action and development. It lays out how governments can strategically engage with the VCM, how carbon accounting can be transparent and credible, and catalyze investments with broader development benefits that empower and strengthen the rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

Download it here. View the slide deck. Read the press release. Source.

Verra manages the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) Program, the world’s largest voluntary greenhouse gas (GHG) crediting program. Over 1,600 certified VCS projects have collectively reduced or removed more than 500 million tonnes of carbon and other GHG emissions from the atmosphere, many of which are based in developing countries. Verra believes that the perspective of these projects needs to be included in the discussions about the structure of the voluntary carbon markets. Source.