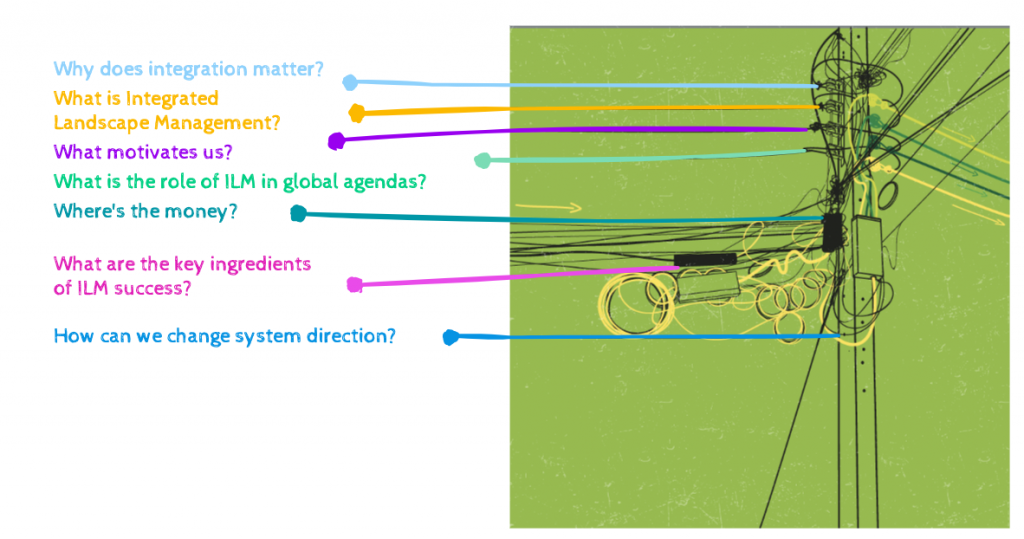

What does it take to make Integrated Landscape Management work in practice?

Practitioners and donors working across Southeast Asia gathered in Bangkok with a shared purpose: to learn, unlearn, and exchange honest reflections. Together, we unpacked what drives success, what holds progress back, and what lessons can guide us into the future.

These insights are highly relevant for implementors worldwide, whether those in our Landscapes For Our Future programme or those shaping new initiatives. Download the illustrated report for a detailed dive or read on for key takeaways that can inform your own landscape efforts.

Executive Summary: Integration, complexity and trust

How might we advance the thinking and understanding of ILM from practice?

As the Landscapes For Our Future (LFF) programme moves toward its conclusion, the Southeast Asia Regional Summit in Bangkok presented an important opportunity to address this question by taking stock of the lessons learned through real-world implementation. Participants were a diverse mix of landscape practitioners, policymakers, and facilitators, yet coherent themes emerged, with a unifying overall message: the landscapes we work in are complex, interconnected systems, and tackling this complexity requires adaptive implementation that convenes people and knowledge. And trust is foundational.

Integrated Landscape Management (ILM) should not merely be another academic term but a practical response to the realities of fragmentation and conflict that have become the norm. At the Summit, participants shared practical experiences of building trust, managing trade-offs, and making inclusive governance work on the ground. These weren’t abstract ideas, but reflections on navigating real challenges in real places.

Even the format of the Summit, which focused on open discussion and participation over formal presentations – reflected the spirit of integration. What emerged was a shared understanding that integration is never finished; it’s a constant, adaptive process of coming together, learning, and adjusting course within an uncertain context.

Key messages and ideas

Importance of local knowledge:

- Leveraging local ecological knowledge (LEK) as a familiar context enhances the effectiveness of management strategies.

- Traditional values and relational knowledge are crucial in fostering community support.

Stakeholder consultation is essential:

- All relevant stakeholders should be consulted during the formulation of projects to ensure their involvement and support.

- Time-consuming yet essential processes like analysis and stakeholder consultation lead to more robust solutions.

Demonstration and evidence:

- Successful case studies and concrete examples serve as models for best practices in ILM, facilitating shared understanding.

- Demonstration sites can effectively showcase the benefits of proposed changes.

Balancing competing interests:

- Strategies must consider the livelihood needs of all actors in the supply chain, creating a win-win situation that includes conservation priorities.

- Addressing land-use conflicts, such as balancing oil palm production and wildlife conservation, is crucial.

Need for adaptive management:

- Flexibility in implementation allows for adjustments based on feedback and changing conditions.

- Continuous monitoring and evaluation are vital to assess long-term impacts and adapt strategies accordingly.

Investment in relationships:

- Trust-building is fundamental; being genuinely interested in the well-being of other stakeholders fosters collaboration.

- Long-lasting partnerships require ongoing engagement and respect for local organizations and structures.

Holistic approach to governance:

- Targeting governance at appropriate scales (national to commune level) enhances the effectiveness of ILM efforts.

- Integrating a global perspective with local contexts is necessary for addressing complex challenges.

This report captures the key themes, reflections, and emerging questions from the Summit. More than a summary, it’s an invitation to keep building the relationships and approaches that make meaningful systemic change possible.

Setting the Stage: Innovation & Integration for Landscape Futures

The opening session set the scene and introduced LFF and the workshop objectives. Notably, participants were NOT introduced to each other through any formal means. At registration, was invited to create their name sticker with any decoration they saw fit, and throughout the event would progressively get to know each other in person. This lack of formalized introduction and hierarchy was significant and key.

As some projects come to an end, what is the concrete value of what we’ve done and lived through? Looking into the future, what is going to be the legacy of this? How can we make sure governments are interested and that we influence policy at national and regional levels? What are the concrete benefits of something like ILM? How can it connect to trends in the global arena? These are questions for us to consider.

– Niclas Gottmann, Policy Officer – Land and Environment, European Commission – DG INTPA

Why does integration matter?

- What do we think landscapes are?

- What does integration look like?

- Why do they matter? What are their benefits?

With the objective of connecting people and focusing them on the question at the heart of the gathering – How might we advance the thinking and understanding of ILM from practice? – participants were asked to draw each other without looking at the paper and ask each other why integration matters. This cycle was repeated twice. (This unconventional and disruptive start to the workshop was based on Liberating Structures’ methodology of Impromptu Networking.)

“There is diversity. How do we get all these groups of people with roles, responsibilities, and influence into a more democratic decision-making process?”

Key messages, phrases and ideas

- “Conflict prevention through ILM.”

- Many participants came from a conservation focus, but had, over the course of their careers, come to integrate the human aspects of landscape more and more.

- ILM provides a way to move beyond silos and “the ability to address diversity.”

- ILM should be “a longer-term investment.”

- “Optimisation of resources: be more inclusive.”

What is Integrated Landscape Management?

- How would you explain ILM to a five-year-old child?

- How would you explain ILM to your potential mother-in-law?

Participants were invited to role-play these explanations as a way to learn how to define ILM in simple terms, without jargon, and using analogies appropriate to their respective audiences. (Based on Liberating Structures methodology: 1-2-4-all and brainstorming.) Innovative analogies emerged: planning a wedding or a children’s party, a house with multiple rooms, sharing pancakes in a classroom…

“We don’t do that often: explain complex concepts. It’s what we should be trying to do more.

Key messages, phrases and ideas

- “How often are we centring their perspectives and interests and using their language? It makes me think about how the terminology includes people in these circles but also excludes others who don’t have access to that language. How can we be more conscious of how language communication affects that?”

- “We are all working in very similar roles. But we sometimes get stuck in our own lane.”

- “We use way too many acronyms. If we can’t understand what we are talking about together, how can the project? Sometimes we get stuck on the acronym, and we don’t even know what it means; stuck on terminology rather than what actually matters.”

What motivates us?

- Why do we think that ILM is a best-bet for the planet, its people and the environment?

- Why do we commit to the concept?

- What challenges have we encountered while implementing ILM?

- How did we overcome them?

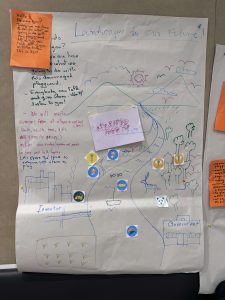

With the aim of getting people to connect at a deeper level and unpack the questions around what motivates them to work on ILM, a series of initial group discussions lead to summaries pasted on the ‘mindmap’ walls for sharing across the groups. (Liberating Structures methodology: Heard, Seen, Respected and Conversation Cafe with a mix of Theory U Learning Circle.) Much of the debriefing conversation riffed on the concept of thinking outside of the box – an analogy that would be returned to frequently throughout the workshop.

To motivate people, you need to be motivated. Every new person gives you energy; every new stakeholder gives you new energy: you go and see the private sector and it gives you new energy. Meeting a lot of people makes you think out of the box.”

Key messages, phrases and ideas

- “It’s becoming this smush of people. We’re all becoming social scientists. We’re recognizing that what’s outside the box is people.”

- “It helps me see the linkage between my personal desire and my personal motivation. Before we speak about thinking outside the box, we need to know the box. The box is my memories that influence my motivation. Some people might have different experiences, different motivations.”

- “How can we take creating these kinds of spaces into our projects and the landscapes?”

- “A lot of time, we stick in the box, but within the box there is a lot of opportunity to take it one step further. You can be creative in the box.”

- “Getting reflections from people who really work in the landscape: everyone is a lecturer for each other.”

- “Motivation is carrot and stick. Are there tools we have not used? We always say we want to influence policy, but how about policy enforcement? We need to think about who can enforce the policies. But, as the community members, we also have lots of space. So that is the stick part. We do want the stakeholders to take full responsibility. We usually apply it to the private sector, but this rule applies to everyone. Nature cannot speak for itself. »

- “We live in an age of information, but it’s the human element, the politics, that we need to try to separate a bit better. How do we move from the information age to the wisdom age? How do we bring all the perspectives together? How can we create some wisdom to make the right decisions?”

What is the role of ILM within global agendas?

- How can landscape approaches contribute to addressing climate change, the SDGs, and global agendas?

- What opportunities are there for us to advance ILM thinking and solutions?

- What are some of the opportunities: what role does ILM play?

- How does the practice of ILM and landscape approaches connect to the various COP conventions and the work under them?

To encourage participants to consider the place of ILM within the subjects of climate change, SDGs and global agendas, and to learn how to motivate for ILM projects in those contexts, participants worked in groups to discuss the role of ILM within the specific COP agendas, as well as to role-play specific project pitches to potential global donors. These exercises proved to be some of the most thought-provoking for participants, pushing them to empathize with the agendas and strictures of more global, external audiences.

Key messages, phrases and ideas

On the role of ILM within global agendas

- On carbon credits: “I’m wondering whether ILM can help to propose alternative verification processes. Are there more democratic and cost-effective ways to deliver verification, such as using the finance to bring communities on board?”

- “Biodiversity: The idea that we see this as a biological challenge and not as a societal challenge is a problem.”

- On the KM-GBF Global 30/30 goal: “The 30/30 goal aims to conserve and restore 30% of the world’s land and oceans by 2030. This presents a significant claim on the land, and how this is done with communities remains variable and dynamic in each national context. ILM can help. Key considerations include determining conservation priorities, engaging communities, and securing funding.”

- On convening at the national level to facilitate global agreements and explore synergies: “There is a great opportunity for the principles of ILM to be applied around convening.”

- On seeking to involve various government ministries, including finance, in biodiversity planning through a ‘whole of government, whole of society approach’: “How does this happen in practice? It’s a challenge. ILM can play a role.”

- On opportunities for biodiversity credits and private sector engagement in biodiversity conservation. “How can we ensure high-integrity credits: What’s the role of ILM here in these market instruments?”

On pitching to global funders

- “When pitching, play on emotional images.”

- “Focus on USPs (Unique Selling Points).”

- “Make it an invitation to join our team.”

- “Suggest matching funds.”

- “Create a story that can connect more to the emotional and human nature. That’s sometimes an element that is helpful in pitches.”

- “Focus on results and envisioned impact.”

- Have a clear product: something palpable. “Something concrete that you can put in our hands. For example, the organic condoms [output from one of the pitches] is palpable for somebody that has invested in it: we’ve got this whole programme and this is what’s coming out of it. I’m holding it in my hands.”

- “INGOs want to solve your problem. The clearer you are about the problem, the more likely they want to help. The problem sells itself.”

- “A participatory engagement process can mitigate risk to the funder.”

- “Highlight problems to be solved and high stakes!”

- “Clear problem analysis at the start!”

- “Include an element of new.”

- “Avoid acronyms.”

Where’s the money?

- How can we look at ILM finance differently?

- What opportunities do these different perspectives offer?

- What are our opportunities to advance or scale ILM thinking and practices?

- What levers can we pull?

To demonstrate the economic values of ILM, including as a financial resource rather than only as an approach that needs financing, Peter Cutter, Director of RECOFTC Program Coordination and Technical Services, took on the role of interviewer in a conversation with Jessica Mauer, Program Coordinator for Lao PDR’s ECILL programme. (Liberating Structures methodology: Celebrities interview.)

Key messages, phrases and ideas

- “Carbon is one of many ecosystem services. Look to value within our landscapes rather than just external resources coming in. In many carbon sequestration projects, because carbon benefits people all over the world, people are willing to invest in a single landscape from the outside and reward the value that ecosystem service carbon creates.” But…

- Carbon scepticism: “We saw a huge dip starting about 18 months ago. Investors got cold feet when credible data showed many claims were overblown. That’s lead to some very good steps. It was a little bit of a reset. It’s not the goldmine we once thought it was.

- On associated benefits: “We had a watershed management programme funded which has changed farmers’ incomes because specialists such as soil scientists come in.”

- “Ensure the legal and policy framework – communities don’t have the money for this.”

- “Embed sustainable financing in all that we do. Often, we need to think about the quality, rather than the numbers.”

What are the key ingredients for ILM success?

- What does ILM ‘success’ look like?

- From our experience, what has been a success?

- Why did it happen?

- How did we get there? How did we know we got there?

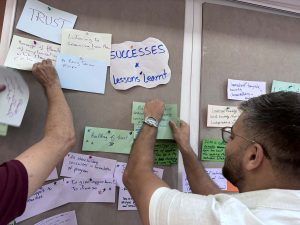

A session focused on celebrating our wins and drawing lessons learnt from our practices employed Liberating Structures Appreciative interviews to discover and build on the root causes of success.

Key messages, phrases and ideas

Trust: Perhaps the greatest ‘aha’ of all from this workshop was this being identified as THE key element for ILM success, and yet how few strategies are deliberately employed to engender this.

The following list of ingredients of successful ILM (in no particular order) emerged through the sticky notes mind map and surrounding discussion:

Training and capacity building:

- Small-scale practical training (e.g., bookkeeping) to enhance skills within communities.

Continuous learning and knowledge documentation to adapt and improve practices.

Financial strategies:

- Access to low-interest credit and micro-finance options for local stakeholders.

Co-investment from multiple parties, including private sector engagement, to support sustainability.

Community engagement and participation:

- Involving local stakeholders in decision-making processes to ensure their needs and perspectives are respected.

Increasing participation from various villages and establishing guardian villages for local stewardship.

Long-term commitment and support:

- Recognizing that change takes time and requires long-term investment and support.

Commitment from all stakeholders, with clear responsibilities laid out through Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs).

Integration of sustainable practices:

- Balancing conservation efforts with income generation, such as transitioning from poaching to ecotourism.

Promoting community forestry and sustainable land use practices for enhanced livelihoods.

Effective governance and collaboration:

- Utilizing existing governance structures to generate buy-in and support for ILM initiatives.

Building durable networks that facilitate ongoing information flow among stakeholders.

Adaptability and flexibility:

- Being open to learning and adapting practices based on community inputs and socio-cultural contexts.

Implementing initiatives that are flexible enough to meet local needs and realities.

Building trust and relationships:

- Establishing connections with government and other stakeholders to foster confidence and collaboration.

Engaging in activities that prioritize the well-being of all stakeholders to build lasting trust.

The consensus was that, by applying these key ingredients, stakeholders involved in ILM can effectively collaborate, promote sustainable practices, and foster resilience within communities while addressing both conservation and livelihood needs.

How can we change system direction?

To summarize the Central Component’s new thinking on a theory of change, which is grounded in systems thinking and the premise that landscapes are complex systems, Kim Geheb offered a grounding in systems theory, talking about what systems are, why we should focus on them, and crucially: how do we change system direction? (This was the only PowerPoint presentation of the entire workshop.)

As a positioning of Integrated Landscape Management, he argued for phrasing it in systemic terms: the system is heading in the wrong direction. “What we want to do – our mission – is that we want to change system direction. We understand from the outset that our context is complex, and we will evolve our strategies because we are adaptive – that is our implementation structure. And in the middle of this, the key function of the intervention is to convene people and knowledge. Those are the two key things, we think. (We may be wrong.) And we use our strategies – the ones that I’ve already touched on: nimble-footed funding, multi-stakeholder fora and leadership teams.”

Key messages, phrases and ideas

- « The other thing that I should emphasize here is that landscapes are socially produced. This is so important because it doesn’t matter what problem we identify: when you look at the drivers that cause that problem to occur, we understand that somebody somewhere is doing something to cause that problem. And so a behavioural focus is necessary. What are we going to do to change those sets of practices? » – Kim Geheb

- « We misuse the term ‘outcome’ all the time: outcome is a change in human behaviour. If you want sustainability of projects, the Outcome Zone is what you have to focus on, not the Project Zone. You have to shift your focus into the future with your hypotheticals and try. But you don’t get project sustainability just through output delivery. » – Kim Geheb

The last session tied it all together. The idea is to shift focus to behaviour change to try to change the direction of the system. Brings a lot of thinking from the week into a clear framework to explain future work.

Julian Atkinson, RECOFTC